Accessible H2O on Mars – A Critical Review of Current Knowledge

HydrologyReceived 21 Oct 2025 Accepted 24 Nov 2025 Published online 25 Nov 2025

ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Next Full Text

Comparing Forecasting Models for Predicting Infant Mortality: VECM vs. VAR and BVAR Specifications

Received 21 Oct 2025 Accepted 24 Nov 2025 Published online 25 Nov 2025

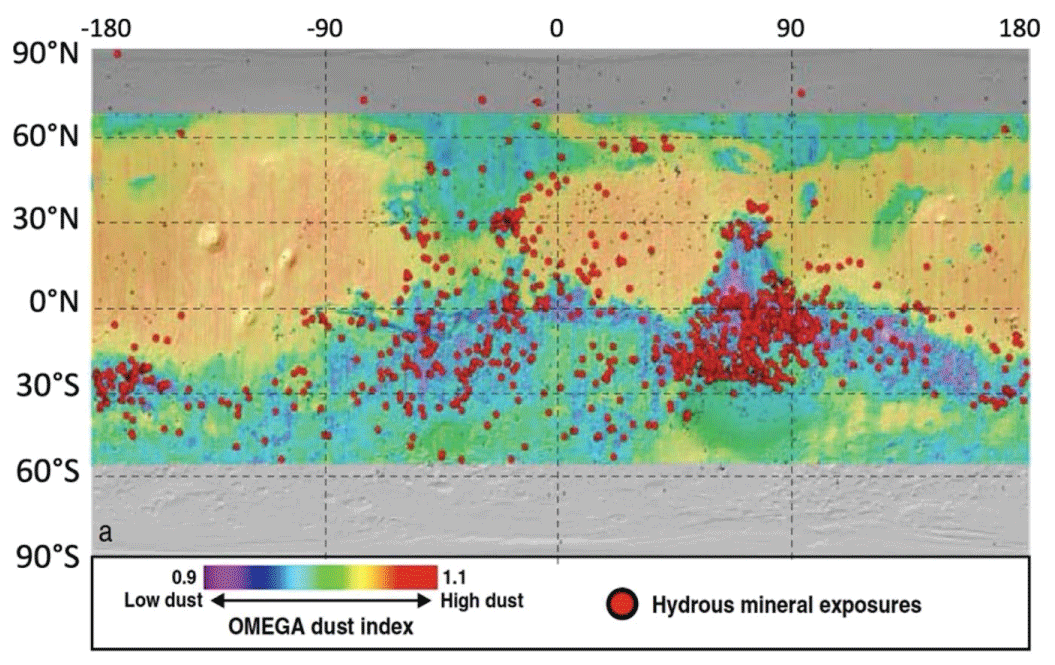

Here, we review what is known about the distribution of accessible H2O on Mars. While “Accessible” in this review implies within about 5 m of the surface, at an elevation at least 2 km lower than the MOLA Datum, and at a latitude within ±20°, possibly extendable to ±30°, we have extended our review to cover observations of H2O at moderate depth within the latitude range ±60°.

Twenty years ago, the neutron spectra and initial ice stability models suggested that ground ice on Mars was likely to be rare equatorward of about 50° latitude. Since then, observation after observation from orbit (using radar, photography and spectroscopy) revealed the likely presence of huge amounts of imbedded ice within the subsurface of Mars, at various depths mostly at so-called “mid-latitudes”. As a result, the pendulum has swung to the point that some enthusiastically suggest that ground ice occurs almost everywhere on Mars. We reviewed the various observations and analyses regarding H2O on Mars. Near-surface ice has been observed, spectra and radar have implied, and ground features have been interpreted to indicate that in wide areas of Mars, shallow ice apparently occurs at latitudes greater than 40° and at a few locations, persists into the 30s. The depths of such putative ice are not well known. Further study with much higher resolution might possibly reveal shallow ice at lower latitudes in unique locations. Mineral hydrates might offer a possible alternative as a supply of H2O.

The search for H2O on Mars has been motivated by scientific investigation into the role (past and present) of H2O in the functioning of the atmosphere-land system, as well as water as a necessary element for life (past or present), and (less often) more pragmatically as a source of support for human missions to Mars via life support and propellant production. In the past couple of decades, many exciting new discoveries were made of widespread H2O on Mars. This generated an aura of enthusiasm for the belief that accessible H2O is there for the finding almost everywhere on Mars. However, much of the “discovered” H2O is based on geological inference from surface formations or radar readings, much of it lies outside the realm of practical use, and still requires verification by “ground truth”.

In this review, we concentrate on the search for H2O that is accessible for utilization by human missions to Mars. In that connection, the three central parameters that guide us as to the which deposits are useful are: (1) latitude, (2) depth, and (3) elevation. In addition, we do not distinguish between the state of the H2O, whether it be ice or mineral hydrates and the depth and ease of extraction. Golombek, et al. [] allowed for higher latitudes up to 40°N as accessible, and they added several other requirements that we did not consider here.

The mission system effects of latitude of landing site on a human mission to Mars do not seem to have been investigated in depth. There is no fixed range of latitude that is widely regarded as acceptable for human missions. Golombek, et al.

[] and Viola, et al. [] considered sites around 39°N to be viable. We have been operating intuitively that ±20° is ideal and ±30° might be acceptable. Some factors that favor equatorial locations are:

(1) Even though solar power is likely to be a secondary source of power, it might be an important backup and useful for outlying locations.

(2) While local air temperatures are more dependent on thermal inertia than latitude, other factors being equal, temperatures near the equator are expected to warmer. Stress on thermal and structural design and control of habitats, rovers, etc. would be less near the equator.

(3) Seeing the (weak) sun would have remarkable psychological benefits for the crew. At 40° latitude, the (weak) sun is only 25 degrees above the southern horizon on Dec. 21.

(4) There are several factors regarding entry, descent and landing (EDL) and ascent trajectories and propellant requirements. Ascent propulsion at lower latitudes requires less propellant.

(5) The changes from season to season are less at lower latitudes - allowing thermal and energy management design to be simpler.

The appropriate range of acceptable latitudes for a landing site remains a point of controversy.

There is also no firm maximum acceptable depth of the resource, but the closer to the surface the better. Obviously, resources right at the surface are ideal. Ice or mineral resources at depths to perhaps 5 m ought to be accessible in the near term. Hydrated mineral resources on the surface would be ideal. In a distant, hypothetical SpaceX large-scale settlement, drilling down 500 m might even be conceptually possible. For our purposes, thinking about the first human mission to Mars, we focus on resources in the upper 5 m.

Sites with elevation at least 2 km lower than the average elevation on Mars (MOLA Datum) are greatly preferred to enhance entry, descent and landing (EDL). The Golombek, et al. [] study listed potential sites ranging from -3 km to -3.9 km relative to the MOLA Datum.

In summary, “accessible” in this review suggests within about 5 m of the surface, at an elevation at least 2 km lower than the MOLA Datum, and at a latitude within ±20°, possibly extendable to ±30°. In addition, the deposit must yield large amounts of water (up to 1,000 MT for the near-term SpaceX mission, and a great deal more for futuristic scaled-up “settlement” missions).

Nevertheless, we reviewed the observations of H2O on Mars ranging from 60°S to 60°N for completeness, since not firm limits on latitude of landing site exist.

Against our limited criteria, many of the apparent discoveries of ice on Mars, though scientifically very interesting, are of dubious practical value. One example is the deposits interpreted by orbital radar to be vast deposits of ice in the Medusae Fossae Formation (MFF) located on Mars at 12°S–12°N, straddling the equator. This formation, if it is verified to be subsurface ice, would consist of a multi-layer ice-poor upper layer some 300 m to 600 m thick, overlying a thick ice-rich layer. (See Section 5.2). While it is not impossible to conceive of drilling down 300 m or more to access ice, the likelihood of this in the first human mission to Mars seems remote. This vast source of H2O seems unlikely to have practical value this century.

It is unfortunate that some observational reports do not provide information on the latitude and depth of overlayer for the deposits, and the elevation at the site is rarely mentioned. The term “mid-latitudes” is widely used but remains unclear as to the range of latitudes which leads to confusion in interpreting data.

In some cases, ice is observed directly on the surface of Mars by photography. Use of radar infers buried ice because of the dielectric constant of the material, as well as discontinuities revealing layers. The neutron spectrometer detects hydrogen in the top ~1 m, whether due to ice or mineral hydrates. Mineral hydrates contain considerable H2O tied up in their crystal structures. Use of the term H2O covers several possibilities.

NASA’s approach to exploration of Mars has been primarily to search for evidence of past or present life by estimating when and where liquid water flowed in the past, and by landing several rovers to explore a few local areas (range: ~20 km). Most of the planet remains unexplored in any detail. Lacking any serious NASA search for water on Mars, scientists came up with innovative methods to utilize instruments on Mars orbiters to observe or infer water on Mars (neutron spectrometer, radar, visual photography, IR spectroscopy). They were fortunate to observe some outcroppings of ice and surface indications of buried ice by photography – a windfall for the MRO camera. These approaches generated considerable information, yet our accumulated knowledge remains fragmentary and unverified by “ground truth”.

In this review, we attempted to assess what we have learned so far about accessible H2O from the various observations and analyses. Today, the general mood is very optimistic. H2O has been discovered in many locations. But science must be skeptical by nature. We must appraise each claimed discovery of a resource according to its uncertainty, and second according to three basic criteria: (1) latitude, (2) depth, and (3) elevation. That suggests that many indicated resources might not be practical for utilization. The search for accessible H2O on Mars is in its infancy. Much of the accessible H2O remains to be discovered.

For the future, the advent of the Starship offers the possibility of a hundred-fold increase over the present capability for landing payload mass [,]. Using this immense increase in payload offers the possibility of wide synoptic exploration of Mars. We could imagine a mission where the Starship provides a main landing site with an Earth-equivalent laboratory establishment, and a human crew controlling dispersed rovers that examine local areas and send data back to the main site via communication satellites around Mars. The rovers would be controlled with almost no time delay. To explore the vast surface of Mars, NASA would have to adopt two new priorities: (1) Search for accessible H2O to enable production of propellants via ISRU for crew return, and (2) Long distance travel across the surface of Mars by robots or crew. This would enable delivery of samples from wide swaths of Mars to the main site. Alternatively, we could imagine a Starship in low Mars orbit dropping many penetrators into key locations on Mars and observing whether ice occurs in the ejecta.

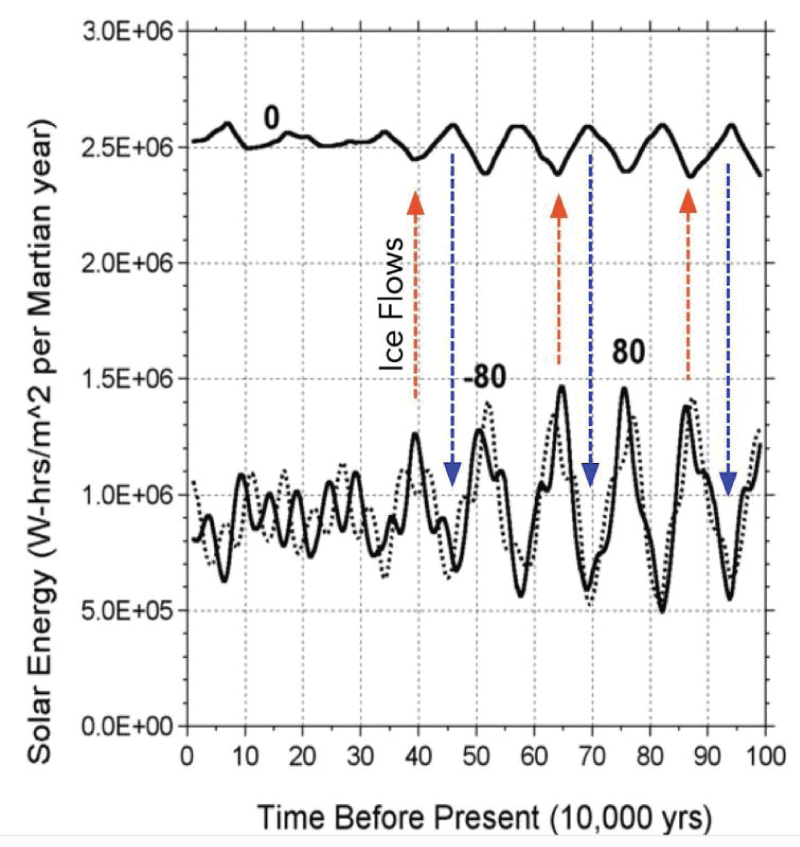

Rapp [] estimated the insolation on horizontal and tilted surfaces for various northern and southern latitudes of Mars over the last million years. Periods of high obliquity increase solar intensities at high latitudes and decrease solar intensities at equatorial latitudes. The percentage effect is much greater at high latitudes. At 80° latitude, the variation in insolation on horizontal surfaces spans almost a factor of three over the obliquity/eccentricity/precession cycle. The variation in equatorial insolation is only about 12%. The difference between the northern and southern highs and lows of insolation is due to the precession of the equinoxes, which continuously changes Lmin (the value of solar longitude (Ls) at which Mars is closest to the Sun). This reversal of which pole is closer to the sun continued throughout the history of Mars with a 51,000-year period.

Rapp [] showed that the orbit of Mars underwent large variations during the past million years. The most important factor was the variation in obliquity, but variations in eccentricity and periodic precession of the equinoxes are also relevant. Such variations would produce major changes in the distribution of solar energy input to Mars as a function of latitude, potentially resulting in redistribution of H2O resources across the wide latitudes of Mars.

A comparison of insolation at the equator on a horizontal surface summed over a Martian year with a high southern latitude and a high northern latitude over the past million years is given in Figure 1 []. The alignment of peaks and troughs at high northern and southern latitudes depends upon the precession of the equinoxes. When Mars is closer to the sun in northern summer, the northern peak is higher, and when Mars is closer to the sun in southern summer, the southern peak is higher. Peaks at higher latitudes are aligned with troughs at equatorial latitudes. Water vapor driven off at high latitudes is captured at equatorial latitudes.

Figure 1: Comparison of insolation on a horizontal surface summed over a Martian year at the equator (0) with a high southern latitude (80°S) and a high northern latitude (80°N). Red arrows show flow of H2O vapor from high latitude toward the equator and blue arrows show return of H2O vapor from equatorial region to high altitudes []. Provided by D. Rapp.

Figure 1: Comparison of insolation on a horizontal surface summed over a Martian year at the equator (0) with a high southern latitude (80°S) and a high northern latitude (80°N). Red arrows show flow of H2O vapor from high latitude toward the equator and blue arrows show return of H2O vapor from equatorial region to high altitudes []. Provided by D. Rapp.Mellon and Jakosky [] extended their landmark 1993 work on the history of water transport on Mars by including a consideration of orbital oscillations and found that moderate changes in the Martian obliquity can shift the geographic boundary of stable ground ice from the equator (global stability) up to about 70° latitude. They also found that diffusion of water vapor is rapid enough to cause similarly dramatic changes in the presence of ground ice at these locations on time-scales of thousands of years or less. It was estimated that the ice content of the upper 1 to 2 m of the soil can vary widely due to exchange of atmospheric water at rates faster than the rate of change of Mars obliquity. They provided an analysis of the behavior of near-surface ground ice on Mars through many epochs of varying obliquity during the past million years. They pointed out that the Mars climate undergoes two major responses to changing obliquity: (1) temperature change due to redistribution of insolation vs. latitude, and (2) increased summertime water sublimation from polar caps during higher obliquity, thus increasing the atmospheric water abundance and affecting the rate and direction of diffusive transport of water vapor in exchange with regolith at various latitudes. It turns out that the increase in atmospheric water abundance is more important than the temperature changes in regard to deposition of ground ice at equatorial and mid-latitudes. A comprehensive thermal/diffusion model allowed mapping out ground ice formation and depletion as a function of depth, latitude and Mars orbital history. Their model described regions and time periods where ice is stable, as well as regions and time periods where ice is not stable, but previously deposited ice remains residual because insufficient time has passed to allow it to sublime. They assumed 40% regolith porosity, allowing a maximum of 0.37 g/cm3 of ice to accumulate.

Transfer of water vapor sublimated from polar areas to equatorial regions is a rapid process compared to the rate of variation of obliquity (many thousands of years). Therefore, it was assumed that an increase in polar sublimation rate is matched by an equivalent increase in mean atmospheric water vapor abundance. They estimated that the atmospheric water content varied by four orders of magnitude when the obliquity varied from 10° to 40°.

According to this model, the mean atmospheric water vapor abundance would be about 35 times greater at an obliquity of 32° than it is today at 25.2°. This raises the frost point from ~ 195 K to ~218 K, and the model allows stable deposition of ice in the regolith at all latitudes. Because of the non-linear dependence of water vapor pressure on temperature, and the direct dependence of diffusion on the water vapor pressure at the surface, when Mars enters into a period of increasing obliquity, the model predicts a relatively rapid spread of ground ice into lower latitudes, culminating in planet-wide stable ground ice at very high obliquities. Subsequently, as the obliquity diminishes with time, the near-surface ground ice is gradually depleted due to sublimation. Therefore, during the past million years, it was concluded that there were periods of widespread ice stability alternating with periods where ice is stable only at high latitudes. Because oscillations of the obliquity of Mars have been relatively small during the past 300,000 years, this period has been marked by unusual stability.

Mellon and Jakosky [] found that "ice accumulates more rapidly during high obliquity than can be lost during low obliquity". Therefore, their curves of depth to the ice table tend to have a characteristic sharp reduction during the early stages of high obliquity, with a longer "tail" extending out as the obliquity diminishes. This appears to be due to the low subsurface temperatures that reduce the vapor pressure and rate of diffusion as the obliquity diminishes. The study provides a great amount of data and it is difficult to summarize all of their findings succinctly. They estimated the regions of ground ice stability and the depths of the ice table as a function of obliquity.

The Mellon and Jakosky study dealt mainly with ground ice that is transported from the polar caps via water vapor through the atmosphere. A permanent layer of such ground ice would be built up below the upper desiccated layer by deposition from the atmosphere to the depth of the seasonal thermal wave where the ground temperature is lower than the air temperature, causing condensation of water vapor in the pores of the regolith. This thermal wave may penetrate perhaps up to several meters. Below that level, the geothermal gradient takes over and the temperature slowly increases with depth, removing the driving force for deposition from the atmosphere. The study concluded that if ice fills the pores of the regolith below this level, it must be ice that was emplaced there a long time ago, and is not part of the periodic exchange process between polar caps and near-surface regolith. At sufficient depths, the temperature will exceed 273 K, and it is possible that liquid water might exist at such depths. However, it would appear that in that case, water vapor rising from these depths will condense out in the sub-freezing regolith below ~ 10 m depth, filling the entire subsurface with ground ice down to the point where T > 273 K. It was suggested that in the pattern of variable obliquity over the past million years, during a period of high obliquity, "diffusion is sufficiently rapid to fill the pore space in the near-surface regolith completely with ice in just a few thousand years." Conversely, as the obliquity falls, they found that "sublimation can be seen to remove ice down to about a meter before the obliquity completes a cycle and again begins to rise." At a latitude of around 50°, they found a steady build-up of subsurface ice in which each period of high obliquity deposits more ground ice than each period of low obliquity removes ice. It is also noted that it is possible that during periods when large amounts of water are alternately ingested and released by the regolith as ice, a cyclic inflation and deflation of the surface might cause small-scale surface features observed on Mars from orbit.

The following conclusions summarize our interpretation of their findings:

The arguments presented above would suggest that ice would have been widely deposited in the regolith of Mars over long periods, and has been slowly escaping from the near surface over the past ~300,000 years. The question of persistence or loss of ground ice over the past ~ 300,000 years when the Mars orbital parameters were relatively stable is discussed in the next section.

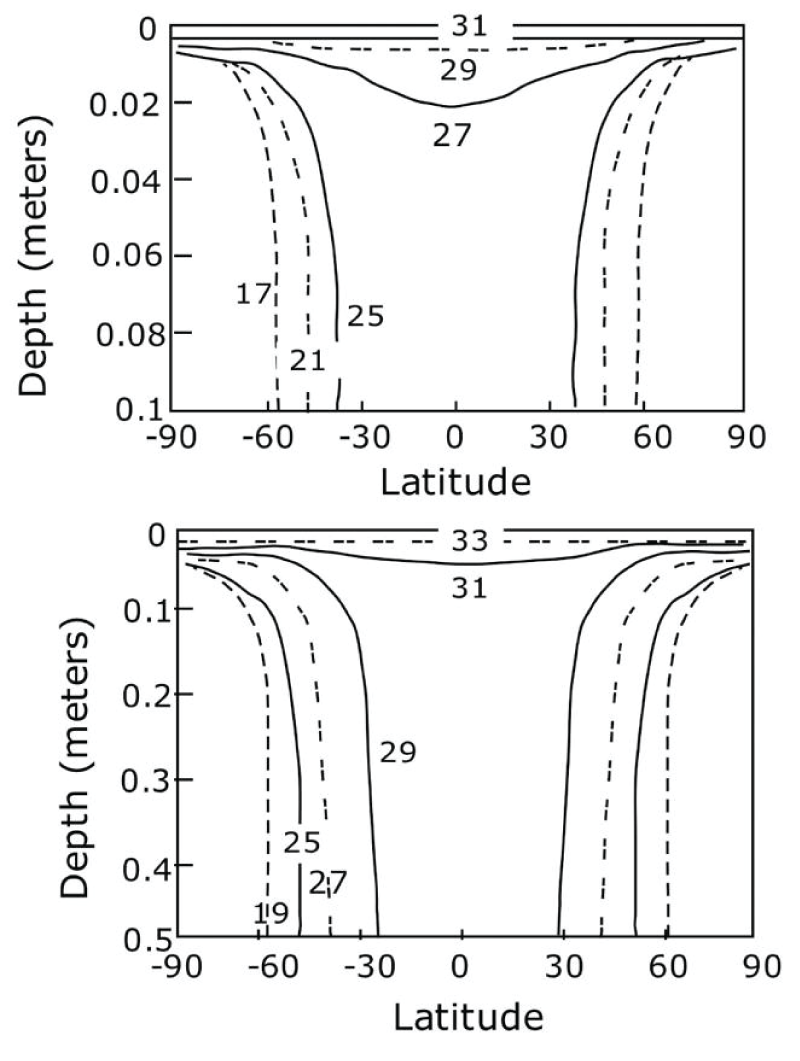

Chamberlain and Boynton [] investigated conditions under which ground ice could be stable on Mars based on the history of changing obliquity of the Mars orbit. They combined a thermal model with a water-vapor diffusion model. The thermal model estimated the temperatures at different depths in the subsurface at different times of the Martian year. Temperatures are functions of latitude, albedo and thermal inertia. The thermal model can determine a depth to stable ice. Ice is stable if the top of the “ice table” has the same average vapor density as the average water vapor density in the atmosphere. H2O is allowed to move by the vapor diffusion model. The temperatures from the thermal model are used to partition water between 3 phases: vapor, adsorbed and ice. Vapor is the only mobile phase and the diffusion of vapor is buffered by adsorbed water. Vapor diffusion models can have ice-poor or ice-rich starting conditions. Vapor diffusion models are run for long periods to check the long-term evolution of depth to stable ice. As ice distribution in the ground changes, the thermal properties of the ground change too. Thermal conductivity increases as ice fills the pore spaces. Vapor diffusion models are run iteratively with thermal models to update the temperature profiles as ice is re-distributed. In one set of results, Chamberlain and Boynton presented data on stability of ground ice vs. latitude for various Mars obliquities. As we pointed out, the obliquity of Mars varied considerably in the past. Two sets of ground properties were utilized:

(a) Bright, dusty ground: (albedo = 0.30 and thermal inertia = 100 S.I. units)

(b) Dark, rocky ground (albedo = 0.18 and thermal inertia = 235 S.I. units).

Their results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Minimum depth to stability of ground ice vs. latitude for various Mars obliquities (a) upper figure: for bright dusty ground, and (b) lower figure: for dark rocky ground. Adapted from Figure 1 of Chamberlain and Boynton [].

Figure 2: Minimum depth to stability of ground ice vs. latitude for various Mars obliquities (a) upper figure: for bright dusty ground, and (b) lower figure: for dark rocky ground. Adapted from Figure 1 of Chamberlain and Boynton [].These results suggest that ground ice is not stable in the current climate at equatorial latitudes due to the low obliquity. However, as the obliquity is increased, a point is reached (depending on the soil properties) where a discontinuous transition occurs from instability to stability of ground ice. According to this model, this transition occurs between 25° and 27° for bright dusty ground, and between 29° and 31° for dark rocky ground. With the present obliquity at 25.2°, ground ice is not stable at equatorial latitudes. As Rapp [] showed, there were several periods in the past million years when the obliquity reached 35°. Even in the stable period of the past ~300,000 years, the obliquity reached 30°, and was as high as 27° only ~80,000 years ago. During those periods, solar energy input to equatorial regions was significantly reduced in winter and solar energy input to high latitudes was significantly increased in summer. It seems likely that there must have been a major transfer of near-surface ice from the high latitudes to the temperate latitudes during these epochs. The obliquity has been ≤ 25.2° over the past ~50,000 years, implying that the subsurface ice deposited in earlier epochs has been subliming, receding, and transferring to polar areas. However, these processes would be inhibited by dust and regolith in some localities. Therefore, it is possible that in some regions, particularly very bright, low thermal inertia regions at low to moderate latitudes, some of this vestigial subsurface ice from former epochs may possibly remain even today, particularly on surfaces tilted toward the poles.

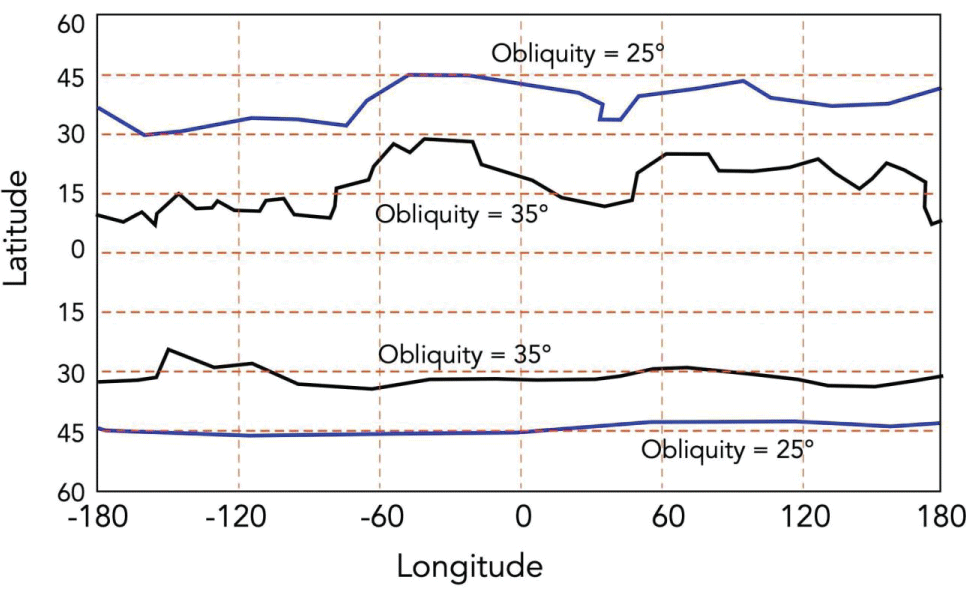

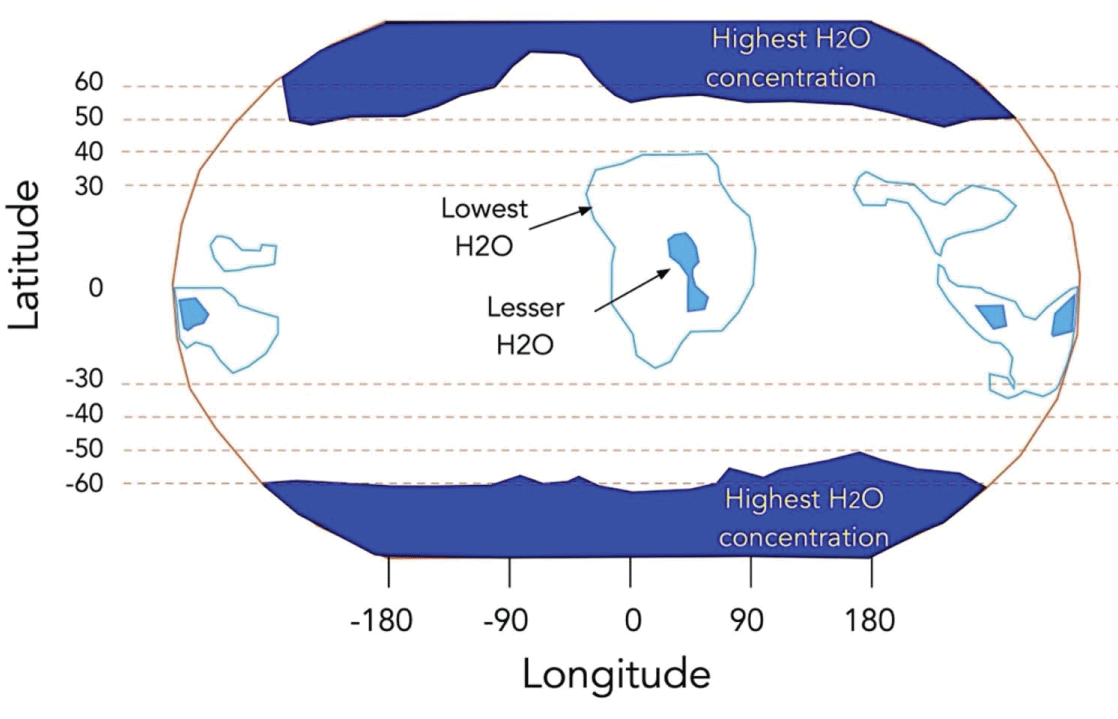

Chamberlain and Boynton [] carried out an updated model of extent of near-surface ice for different ancient epochs. They modeled the atmospheric water content for different epochs on the basis of the water carrying capacity of the atmosphere over surface ice, including s a technique to correct the water vapor density just above the surface for depletion due to nighttime frost, reducing the effective water vapor density in contact with ground ice. This reduced the spread of ice to lower latitudes even at high obliquity compared to previous models. An approximate interpretation of their results is given in Figure 3. The values for obliquity = 25° are appropriate for current conditions. At a high obliquity of 35°, ice can be stable down to fairly low latitudes in the North, but not at the equator.

Figure 3: Approximate interpretation Figure 10 of Chamberlain and Boynton []. The curves show the extent of ice stability for two levels of obliquity.

Figure 3: Approximate interpretation Figure 10 of Chamberlain and Boynton []. The curves show the extent of ice stability for two levels of obliquity.Note: In several of our figures, the longitude is given as -180° to +180°, whereas it is now conventional to use 0° to 360°. We used the designation as given by the authors.

A recent study of the history of ancient water on Mars carbonate formation and surface liquid-water availability are linked by negative feedback that suggests intermittent water “oases” on Mars rather than widespread and persistent water []. This potentially explains the time span, intermittency and patchiness of oases on Mars; the locations and total volume of the sedimentary rocks that entomb those oases; the end of surface habitability on Mars; and the isotopic composition of Mars’s atmosphere. After 3.5 Ga, carbonate formation can regulate the size and duration of oases on Mars.

We have shown in the previous section that great amounts of ice were estimated to have been deposited in the ±60° latitude range in the distant past, and recent observations confirm that some of that vestigial ice remains in the subsurface and near surface of Mars at various locations.

Skorov, et al. [Gourronc M, Bourgeois O, Mège D, et al. One million cubic kilometers of fossil ice in Valles Marineris: relicts of a 3.5 Gy old glacial land system along the Martian equator. Geomorphology. 2014;204:235–255. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2013.08.009.] showed that dusty areas with low thermal inertia enhance the stability of ground ice, at least in upper-mid latitudes.

Mellon and Phillips [] assumed average values for soil properties and atmospheric water content. Based on this, their model indicated that under current Mars conditions, the slope of the surface has a strong effect on the ice table depth in this latitude range. They estimated the depth of the ice table for various slopes and latitudes. They also explored the dependence on the obliquity of the Mars orbit to infer what might have happened in past epochs. They found that when the obliquity exceeds about 31°, there is a rather abrupt transition to a stable ice table at 30°S at a depth of about 2 meters. At higher obliquities, the model indicates that ice table is shallower and exists at all latitudes.

Schorghofer and Aharonson [] carried out an analysis of subsurface ice stability. Their work included two parts: (1) depth of the ice table vs. latitude at equilibrium, and (2) rate of change of subsurface due to changing surface conditions. Model predictions were made for ground ice in thermodynamic equilibrium with the water vapor in the present atmosphere. Temperatures were obtained with a one-dimensional thermal model of the subsurface, using a thermal inertia map, an albedo map, orbital elements, and partial surface pressures obtained from the Thermal Emission Spectrometer over a Martian year. They found that the depth of the ice table ranged from about 20 g/cm2 at 85° latitude to 50 g/cm2 at 70° latitude, to about 100 g/cm2 cm at 60° latitude, and then the depth of the ice table plunged at lower latitudes. These depths in g/cm2 can be converted to linear distance if a density is assumed. For example, if the density is assumed to be 1.5 g/cm3, the depth in cm is the depth in g/cm2 divided by 1.5. They estimated that due to the rapid exchange of water vapor between the atmosphere and the subsurface, small amounts of subsurface frost will accumulate during the cold season down to latitudes of 25°, in a layer below the penetration depth of diurnal temperature variations and above the penetration depth of seasonal variations. Figure 4 shows that in the regions where they estimated that subsurface ice is not stable year-around, it may be stable for part of a year, particularly where the thermal inertia is low. It can be seen that all of the Mars landers so far except VL-2, landed in regions of high thermal inertia where subsurface ice is never stable.

![Fraction of a year for which frost point is higher than subsurface temperature. Background shading shows regions of high thermal inertia. Mars landing sites are shown as circles. The vertical scale is latitude. Adapted from Figure 13 of Schorghofer and Aharonson [].](https://www.igminresearch.com/articles/figures/igmin322/igmin322.g004.png) Figure 4: Fraction of a year for which frost point is higher than subsurface temperature. Background shading shows regions of high thermal inertia. Mars landing sites are shown as circles. The vertical scale is latitude. Adapted from Figure 13 of Schorghofer and Aharonson [].

Figure 4: Fraction of a year for which frost point is higher than subsurface temperature. Background shading shows regions of high thermal inertia. Mars landing sites are shown as circles. The vertical scale is latitude. Adapted from Figure 13 of Schorghofer and Aharonson [].Mellon, Feldman and Prettyman [] also carried out an analysis of ice stability at various latitudes. They made new estimates of ground-ice stability and the depth distribution of the ice table and compared these theoretical estimates of the distribution of ground ice with the observed distribution of leakage neutrons measured by the Neutron Spectrometer instrument of the Mars Odyssey spacecraft’s Gamma Ray Spectrometer instrument suite. Their calculated ground-ice distributions were based on improvements over previous work in that (1) they included the effects of the high thermal conductivity of ice-cemented soil at and below the ice table, (2) they included the surface elevation dependence of the near-surface atmospheric humidity, and (3) they utilized new high-resolution maps of thermal inertia, albedo, and elevation from Mars Global Surveyor observations. All of their results scale with the fundamental (but still uncertain) parameter: the global annual average precipitable water vapor. Comparison of their results with neutron spectrometer results from Mars Odyssey suggests that this parameter is between 10 and 20 pr µm with outer bounds of 5 and 30 pr µm. For the case of 10 pr µm, their results indicate that the ice table reaches ~1 m depth at latitudes northward of 50 ± 5° north latitude, and southward of 55 ± 5° south latitude. If the global annual average water vapor concentration is as high as 20 pr µm, the latitudes where the ice table is at 1 m depth would shift about 4° toward the equator.

Vincendon, et al. [] used various modeling hypotheses and reached the conclusion that water ice is present within one meter of the surface on all 20°–30° pole facing slopes down to about 25°S. Note that 20°–30° slopes are extreme, and are unlikely to be practical for a landing site. The model depends on the fact that CO2 ice is not observed to persist down to these levels, suggesting a heat source that they attribute to hypothetical near-surface ice.

Mellon and Sizemore [] modeled ground-ice stability in the upper meters of the soil on Mars for the past 2.5 Myrs at relevant sites. They concluded that in the geologic past, ground ice was likely globally stable and present in the top 10 cm of the soil as recently as 500 kyrs ago. They concluded that ground ice may be stable today for conditions that favor cooler ground temperatures. These conditions include high pole-facing slopes and soils that exhibit high albedo and low thermal inertia. Where ground ice is unstable, relict ground ice may persist in a state of disequilibrium tens of meters below the surface.

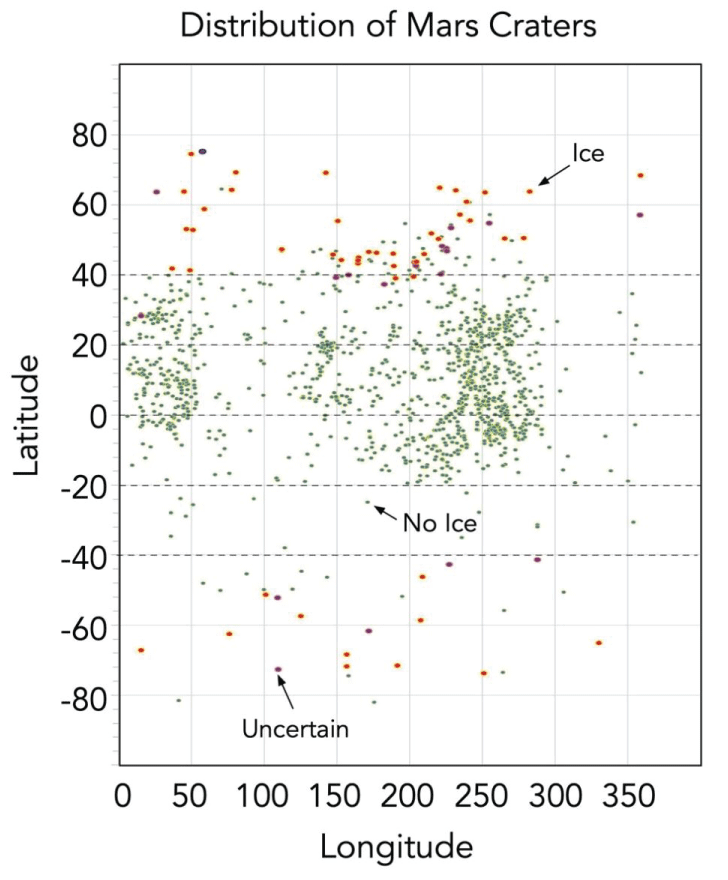

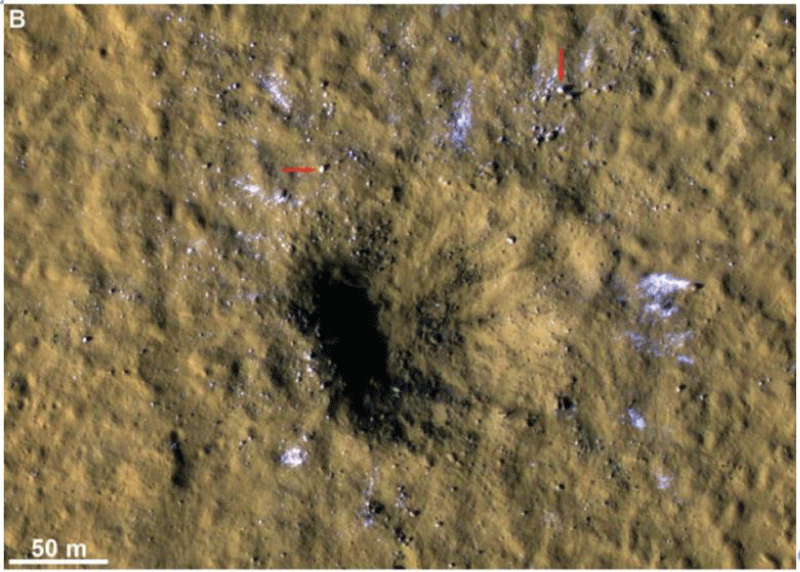

Lange, et al. [] revisited earlier models of ice stability at sub-tropical latitudes (25° to 30°). They pointed out that ice is not expected to be stable on horizontal surfaces at these latitudes, “but could be stable on pole-facing slopes which have cold microclimates”. They developed a new model to examine this possibility. Their Figure 3 shows the theoretical stability of subsurface water-ice with respect to diffusion for flat surfaces and for pole-facing 30°slopes using a nominal near-surface humidity. While the exact contours of stability are subject to the uncertainties inherent in such models, the difference between a flat surface and a sloped surface is impressive and that difference is likely to be real. For pole-facing 30° slopes, the model predicts widespread stability at latitudes greater than 44°. It is also noteworthy that their Figure 3 indicates that for pole-facing 30° slopes, ice is never stable at 30° latitude, and only rarely stable below 40° latitude. As an aside, we mention that it is common in these contour plots to also show dots where ice was exposed by impacts or scarps as experimental evidence to go along with the theoretical model. However, that might create a false sense of prevalence of ice because 96% of the craters did not show ice, indicating that such exposures of ice are sporadic and scarcely distributed amongst dry areas []. It is also important to note that a 30° slope corresponds to a 58% grade, rarely occurs, and is unsuitable site for a human landing.

The obliquity of Mars is presently 25.2°. Over very long time periods, the obliquity of Mars in its orbit has varied widely, affecting the global stability of near-surface ground ice. Models indicate that there is a great sensitivity of stability of ground ice to the obliquity, and at some point, with obliquity above roughly 27°, ground ice can become widely stable, even at some temperate latitudes. Since the obliquity exceeded 30° in the past million years, models indicate that ground ice was likely deposited in the North down to as low as 10° to 15° latitude, and in the South as low as 30° latitude in that time period. The models utilize quantitative approximations and assumptions but there is little doubt that the trends are correct. Over the past 300,000 years, the obliquity of Mars has been relatively stable. During that period, ice embedded in the Mars regolith has been diffusing out, leaving behind a patchwork quilt of occasional deposits of remnant ice and dry soil, mostly depleted at low latitudes, and increasing in coverage at higher latitudes until ice is widely prevalent above perhaps 50° latitude, and scattered at various locations at lower latitudes, becoming less prevalent below 40° latitude.

The model results depend on the orientation and properties of the surface. Regions with low thermal inertia will retain ground ice longer. Equally important is the slope of the surface, and if steep and facing North, might preserve ancient deposits of ice to this day.

From a pragmatic point of view, the greatest interest is in residual near-surface ice within the ±30° latitude range where future human missions to Mars are likely to be based, and the closer to the equator, the better. However, some researchers are willing to stretch a point and even consider mission locations in the 35° to 40° latitude range [].

The models are better at estimating where ice may have been stable in the distant past at higher obliquity but are not as good for estimating how much remains at low latitudes where ice is presently not thermodynamically stable, but might persist due to slow kinetics. Observations of indigenous H2O on Mars must be used to estimate current ice resources, and that will be reviewed in the next sections of this report.

The Mars Odyssey Orbiter carried neutron and gamma ray spectrometers for observation of Mars.

The following description is adapted from Boynton, et al. []:

Cosmic rays strike atomic nuclei in the matter in the surface of Mars, and generate neutrons by various nuclear reactions. The neutrons then lose energy by collision with surrounding nuclei, and thus excite other nuclei, which then de-excite by emission of gamma rays. After the neutrons lose enough energies to approach thermal energy, they can be captured by nuclei, which then also de-excite by emission of gamma rays. Some of the neutrons escape the planet’s surface and can be detected in orbit. The flux of these leakage neutrons is indicative of the amount of moderation and capturing of the neutrons. These processes are a function of the composition of the surface because different elements have different cross sections for capture and have different abilities to moderate neutrons. Hydrogen is especially effective at moderating neutrons because its mass is nearly the same as that of the neutron. Neutrons are conventionally divided into three different energy bands: fast, epithermal, and thermal.

These energy bands are thermal (energies less than 0.4 eV), epithermal (0.4 eV < E < 0.7 MeV), and fast (0.7 MeV < E < 1.6 MeV) neutrons.

By measuring the flux of neutrons in each energy band, it is possible to estimate the abundance of hydrogen in the upper ~ 1 meter of Mars, thus inferring the presence of water. However, the hydrogen will be obscured if there is a surface layer of carbon dioxide ice.

The neutron spectrometer (NS) (in orbit) returns several neutron spectra and a gamma ray spectrum about every 20 s, which is the equivalent of one degree of motion or 59 km over the surface. The data are then binned over regions of interest to improve statistics. For much of the data reduction, the data were binned in 5° latitude bands to improve signal-to-noise so the pixel size is effectively about 550 km. The data records only the abundance of hydrogen regardless of its molecular associations; however, the results are reported in terms of water-equivalent hydrogen (WEH) mass fraction (WEH is the weight percent (wt%) of water that the subsurface material would contain in the almost certain possibility that the detected hydrogen is present as some form of H2O – ice or mineral hydrates).

Relating this data to the actual distribution of H in the surface is not straightforward. If the flux of neutrons is constant and hydrogen is uniformly distributed with depth, then the concentration of hydrogen is directly proportional to the gamma ray signal strength. Since the hydrogen concentration can vary with depth, the relation between concentration and gamma signal is complex. Similarly, if there is a single layer with constant water content, the neutron fluxes can be estimated as a function of water content. However, if as is almost certain to be the case, vertical distribution of water content is variable, the dependence of gamma ray and neutron signals on the water distribution function is also complex. The raw data (counts) can only be converted to water content for a specific model of vertical distribution. For all models, it is assumed that the concentration of elements other than H was that of the soil measured by the Mars Pathfinder Alpha Proton X-Ray Spectrometer. In the original work, the results were normalized to unity for a soil with the equivalent of 1% H2O by weight at the location of Viking I. In subsequent work, normalization was accomplished by using counts from a polar area covered by a CO2 cap (that acts as a shield) as a "zero" base. This made a small change in the normalization (basically the 1% minimum rises to 2%).

The model used to process most of the data was a two-layer model in which a desiccated upper layer of thickness D containing 2% water by weight, covering an infinite slab containing X% water by weight. The neutron count rates can be estimated by detailed modeling for any values of X and D. There are two parameters involved, and in the more recent treatment, use was made of neutrons with different energy to attempt to resolve X and D.

4.2.1 Introduction: Assuming a simple two-layer model, with the upper layer containing ~1% water, the fluxes of thermal and epithermal neutrons were modeled as a function of the thickness of the overburden of desiccated regolith (in g/cm2) for various settings of the water content (% by weight) in the lower layer []. A similar set of curves was generated for the upper level containing 2% water. It was found that the 2% curves fit data better at higher latitudes and the 1% curves fit better at lower latitudes. For high latitudes, the data indicated a lower layer water concentration of perhaps 35%. The thickness of the upper layer appeared to vary typically from about 20-50 g/cm2 at higher latitudes (60 - 80°) to over 100 g/cm2 at 40° latitude.

Further analysis provided a revised procedure for data reduction []. It was necessary to remove data that was contaminated by seasonal deposits of CO2 frost, by separating the total data set into three parts. The data measured before the autumnal equinox in the south (corresponding to an areocentric longitude of Ls ~ 0) was used to generate the portion of the data set poleward of about 60°S latitude. A similar procedure for the northern boundary used data measured after Ls = 100. Data within the middle band of latitudes (~-60° to +60°) was averaged over the entire data set. Correction of all counting rates for variations in cosmic ray flux, global variations in atmospheric thickness. Corrections were also made for variations in atmospheric thickness due to topography at mid-latitudes.

The initial analysis normalized the data against the Viking I site data that indicated ~1% water content in the upper layer. In that work it was found that data fits to models were best when the upper layer had about 1% water content at mid-latitudes and about 2% water content at higher latitudes. In the new analysis, calibration was made against areas covered with CO2 ice that should have no hydrogen signal, and this led to adoption of a uniform 2% water content for the upper layer at all locations.

As before, both a single layer and a two-layer model were utilized. The two-layer model utilized an upper layer of depth D (g/cm2) with 2% water content by weight, and a lower layer of infinite thickness containing X% water by weight. Since the neutron data are not sensitive to depths deeper than ~ 1–2 m, any assumptions made regarding water content below ~ 1–2 m are irrelevant. Unlike the initial analysis that used thermal and epi-thermal neutron data, the revised data analysis combined the data on epi-thermal and high-energy neutrons. Although a preliminary analysis showed that thermal neutrons should be more sensitive to burial depth than fast neutrons, the authors purposely avoided them at this point because a unique interpretation of thermal neutrons requires knowledge of the composition of surface soils (specifically, the abundances of the strongest neutron absorbers, Fe, Ti, Cl, Gd, and Sm). These abundances were not available to Mars Odyssey gamma-ray observations.

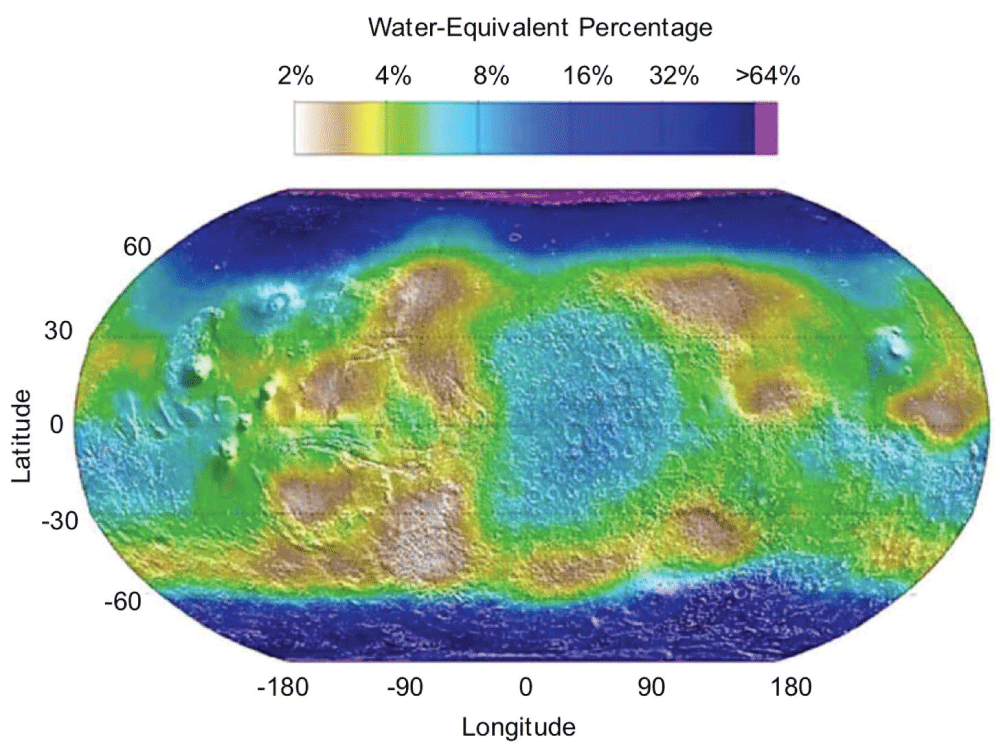

Based on the simple model of a uniform regolith (no layers) containing an unknown mass fraction of water, and utilizing only epi-thermal neutron data a global estimate of water content was made assuming that the lowest water concentration is ~ 2%, as shown in Figure 5 The effect of a two-layer model with 2% water in the upper layer on Figure 5 will lead to increased water concentrations in the lower layer compared to those estimated for a single layer. For middle latitudes (-45° to +45°) it was estimated that the correction to the data in Figure 5 is given by:

Water fraction (lower of two layers) = 0.998 (water fraction in figure) + 1.784 (water fraction in figure)2 + 0.000435.

For a region with say, 10% water according to the figure (water fraction = 0.10), the estimated water content of the lower layer in a two-layer model is

0.0998 + 0.0178 + 0.0004 = 0.118 or 11.8%.

This estimate was based on a 10 g/cm2 upper layer. If the upper layer is thicker, the correction would be greater.

We were unable to derive the uncertainties in these measurements. We suspect that the linearity of the scale is uncertain, and the lower values of WEH might not be as precise as the higher values?

Figure 5: Global variation of water content in upper ~ 1 m of Mars based on a uniform regolith model (no layers) using epi-thermal neutron data. Adapted from Figure 4 of Feldman, et al. 2004 [,].

Figure 5: Global variation of water content in upper ~ 1 m of Mars based on a uniform regolith model (no layers) using epi-thermal neutron data. Adapted from Figure 4 of Feldman, et al. 2004 [,].4.2.2 Mars odyssey observed water content based on a two-layer regolith model at equatorial and mid-latitudes: A first-order approximation to the depth of burial of the lower H2O-containing layer can be made through a combined study of epithermal- and fast-neutron counting rates. Processing data from epi-thermal neutrons with an assumed uniform regolith model will underestimate the water content in the lower layer of a two-layer model. The fast-neutron indication of water content will be lower than the epithermal indication of water content because the fast signature of hydrogen drops off more rapidly with depth and generally, there is more water at depth than there is near the surface. As the thickness of the uppermost desiccated layer increases to a value greater than about 100 g/cm2, both the epithermal and fast neutron curves flatten out to a constant prediction of 2% H2O. In other words, a water-rich soil layer buried beneath a relatively desiccated layer can no longer be detected from orbit through measurements of escaping neutrons if its physical thickness is larger than about one meter.

Models were developed to define the relationship between the apparent mass fraction of H2O from measured fast neutron currents to that determined from measured epithermal as a function of water content in the lower layer and thickness of the upper layer. The results are provided in Figure 5. As Figure 5 shows, there are three places in the equatorial zone where the simple uniform regolith model predicts water mass fractions as high as ~ 10%. The two-layer model was used to elucidate more insight into these, and other equatorial and mid-latitude sites. For this purpose, the measured counting rates equatorward of ±45° were binned into 5° latitude quasi-equal area spatial elements (about 550 km x 550 km). The data analysis indicates that most of the water-equivalent hydrogen at near-equatorial latitudes is buried below a desiccated layer. The preponderance of data suggested an upper layer thickness of typically 10-20 g/cm2 with occasional locations going up to 40 or even 60 g/cm2.

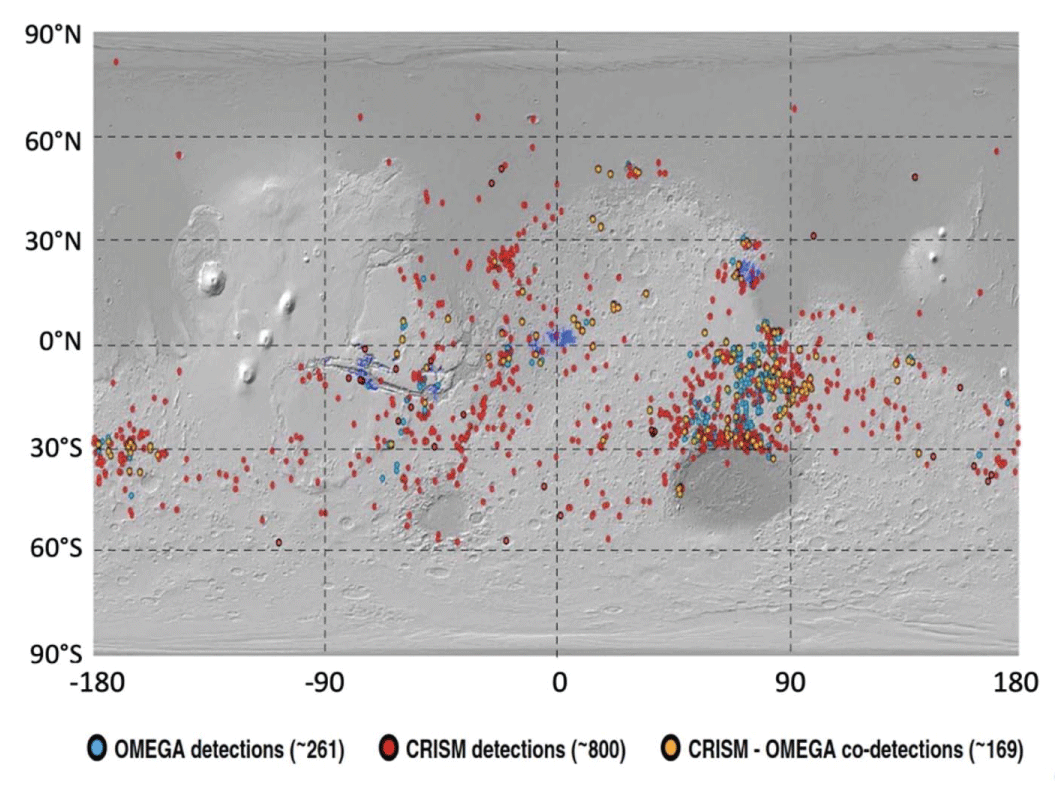

Karunatillake, et al. [] showed that the distribution of near-surface sulfates on Mars is similar to the distribution of H2O shown in Figure 5, suggesting that lower latitude H2O is likely to be due to sulfate hydrated minerals (rather than ice).

Pathare, et al. [] developed an updated analysis of the data. This data was plotted by Butcher [] as shown in Figure 6. When you compare Figures 5,6, they are quite similar but the later plot (Figure 6) shows a little more definition.

Figure 6: Simplified version of updated plot of Mars Odyssey data. Adapted from data in Figure 7 of Butcher [].

Figure 6: Simplified version of updated plot of Mars Odyssey data. Adapted from data in Figure 7 of Butcher [].The acquisition of this synoptic data from Mars Odyssey represents a major step forward in our understanding of the distribution of near-surface hydrogen on Mars. Whether the data and ensuing analysis is sufficient to quantify water percentage is arguable, but as a minimum, the data distinguishes between areas heavily laden with ice, areas with moderate amounts of hydrogen (ice or mineral hydrates), and areas with minimal amounts of hydrogen. The areas with lower estimated percentages might be less accurate than the areas with higher percentages. The limitations due to the 550 km pixel size are significant in regions where there is a small but significant water equivalent percentage (~10%). It is impossible to distinguish between a broad field containing ~10% vs. several distributed localities with high concentration embedded in a background field with low percentage.

4.2.3 Interpretation of depth from mars odyssey neutron measurements: There is direct correspondence between the energy of a registered neutron and depth at which it was produced. The production rate of gamma rays from fast neutrons has a maximum at depths less than tens of centimeters while the epithermal neutrons originate from a layer 1-3 m below the surface. Combining measurements in epithermal energy range with measurements above 1 MeV, the water abundance distribution at different depths can be constructed starting from thin subsurface layer and going down to a meter or two in depth. This allows checking simple models describing the layered structure of the regolith.

To extract information on regolith structure from neutron data, Mitrofanov, et al. [] implemented two typical types of regolith models. One used a homogeneous distribution of water with depth. The second utilized two layers with relatively dry (~2% of water) upper soil layer covering the lower water-rich layer. In the first model there was only one free parameter – water content. In the second model there were two free parameters: thickness of the upper layer and water content of the bottom layer. The calculations were restricted to selected high latitude provinces of Mars. Some wet equatorial regions inside Arabia Terra were also investigated to find regions of highest water content at equatorial latitudes, although no specific graphical data were presented for this case. The footprint size was typically 550 km × 550 km. They said that only the two-layer model fits the data.

Mitrofanov, et al. [] mentioned data that provided estimates of depth to the ice-filled layer, and the water content of the ice-filled layer. The original paper where that data was published cannot be found but Rapp [] presented the data. Soil depths in the North Polar Region are small (0-15 g/cm2 above 70°N) and increase as the latitude is decreased. In the South, soil depths are a bit greater (15-20 g/cm2 pole-ward of 70°S) but water content is similar. However, the water content drops more sharply than in the north near 60° latitude.

4.2.4 More recent data processing of mars odyssey data: Wilson, et al. [] revisited the Mars Odyssey data and improved the map’s spatial resolution approximately a factor of two (from 550 km to ~ 275 km) via a new pixon image reconstruction technique. They presented maps of the near subsurface hydrogen distribution on Mars based on epithermal neutron data from the Mars Odyssey Neutron Spectrometer. They focused on a few locations that have been proposed to contain water deposited in the geologically recent past in equatorial regions of Mars. In the ±30° region, the higher resolution revealed some areas with more hydrogen than at lower resolution. However, even the highest hydrogen areas in the ±30° region appeared to be limited to about 10% to 12% WEH. There is no way to determine whether this is due to ice or mineral hydrates but it seems most like to be mineral hydrates from other considerations.

They also compared a local part of the synoptic orbital data around Gale crater to the data taken by the Dynamical Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) instrument on the Curiosity Rover [].

They concluded that “at low and equatorial latitudes we found evidence, in the reconstruction of the MONS data, for buried water ice in the Medusae Fossae Formation and on the western slopes of the Tharsis Montes and Elysium Mons”. We think this conclusion is insupportable from the evidence.

The FREND instrument (Fine Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector) is installed onboard the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) of the Russian-European ExoMars mission, launched in 2016. Currently TGO's science orbit is circular with an altitude of 400 km and an inclination of 74°, thus the FREND does mapping of the surface between 74° latitude north and south. FREND's major new characteristic is its neutron collimator – a passive system significantly limiting the instrument's field of view (FOV). FREND has two detection systems with collimated FOV: Detection System for Epithermal Neutron (DSEN) and Detection System for Fast Neutrons (DSFN). The results reported by Malakhov, et al. [] were obtained from the DSEN data.

The major innovation of the FREND instrument is its collimator that shields detectors to a narrow field of view, thus producing maps with higher spatial resolution than were observed previously with omnidirectional neutron spectrometers. The results are reported as wt % water equivalent hydrogen (WEH). Because of the narrower field of view, the instrument had to observe longer to get sufficient counts per pixel.

Malakhov, et al. [] reported new water content maps in the upper meter of the regolith from epithermal neutron telescope on the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter. In order to standardize their data, they selected a baseline as a very dry region of Mars (the Solis Planum region between 115° W and 65° W longitude and 55° W and 15° W latitude) that had previously been estimated to average about 2.78% WEH and set the count rate there as equivalent to 2.78% WEH. This differs from the assumption used for Mars Odyssey, but it only slightly changes the scale.

The spatial resolution of the Mars Odyssey instrument was about 550 km. The FREND DSEN claims to achieve resolution of 200 km, but in a few extraordinary cases, it is claimed to drop to as low as 60 km, depending on the amplitude of neutron flux variability and available statistics, as well as any a priori information on the contour of the measured area (where the contours of WEH can be aligned with the higher resolution of the land contours). It is claimed that the 200 km resolution can be achieved anywhere on Mars, and the 60 km resolution can only be achieved in some local areas where there is high variability along with independent data on the shape/size of the measured area. This is an important improvement compared to previous neutron detectors in the Martian orbit, that were all omnidirectional and measured neutron flux from horizon to horizon.

The authors emphasized that “FREND, and all other orbital neutron spectrometers, are statistical instruments, meaning that measurements of any surface feature should be performed with sufficiently long exposure times before an acceptable number of counts is accumulated for a high enough statistical significance. Thus, it is evident, that as FREND was operating and accumulating data in each surface element (or pixel) over Mars, more and more features become detectable.” In an affiliated paper, they focused in on one area – Valles Marineris []. We discuss this later in this section. In Malakhov, et al. [], they providing the first global survey – a high spatial resolution equatorial map of water distribution in the upper meter of the Martian regolith, observed between May 2018 and November 2021 (total 1287 Martian sols, close to 2 Martian years).

Here we review some findings by Malakahov, et al. [].

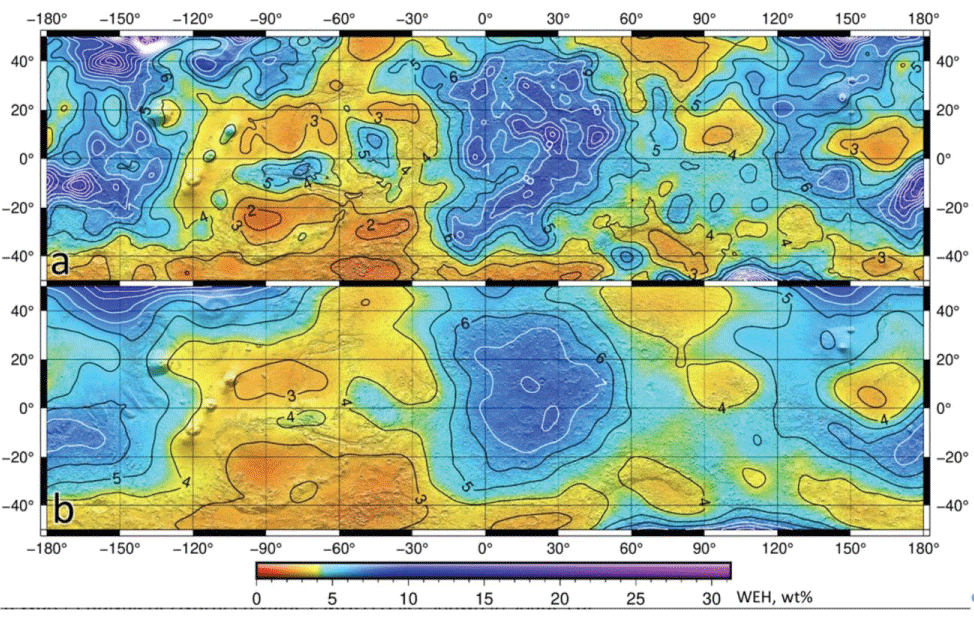

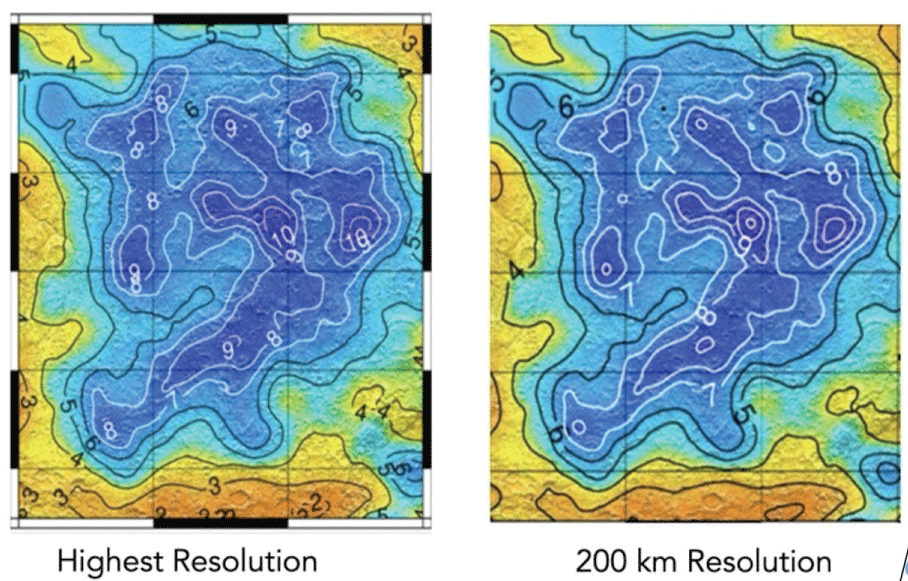

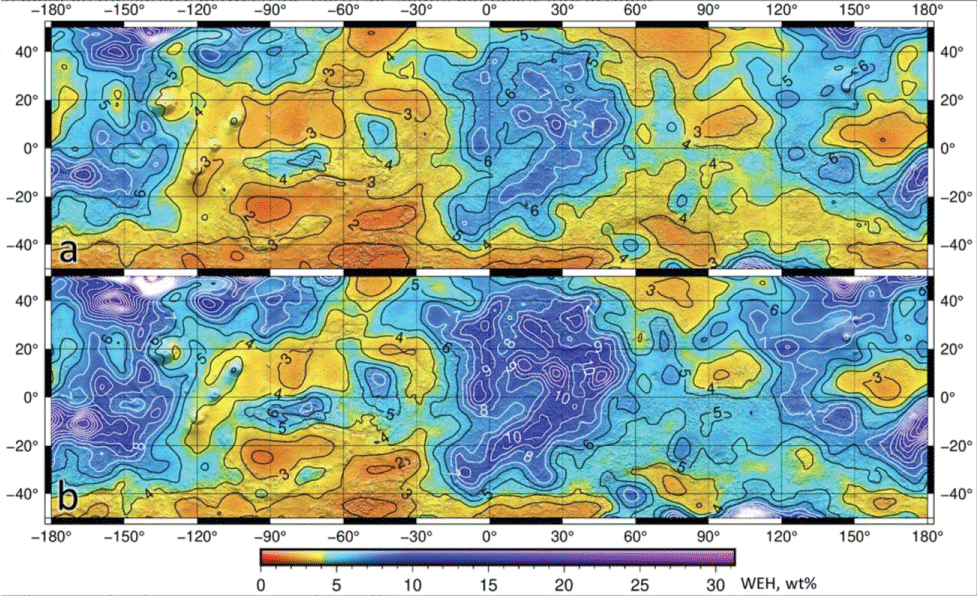

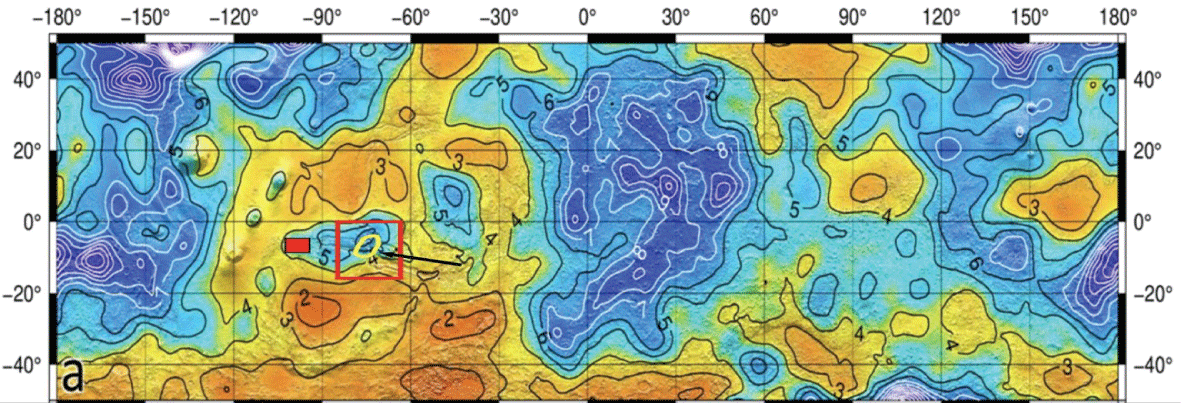

Figure 7 provides a comparison of the higher resolution map (200 km) to the omnidirectional map (550 km). Unlike the study by Wilson, et al. [] where the higher and lower resolution images did not correlate well, the FREND/DSEN hi-res and low-res maps correlate very well, and one can easily visualize how one leads to the other as the resolution is increased. It is notable that throughout the entire realm of longitude, and the latitude range ± 50°, the highest value of WEH in the higher resolution plot is 8%. However, notice that the highest WEH in the lower resolution plot is 6%. This shows that smaller local areas with higher WEH become diluted at lower resolution because they are averaged with areas of low WEH. Therefore, we can expect that as the resolution is further reduced from 200 km, the maximum of 8% will increase in some small areas.

Figure 7: Water equivalent hydrogen maps, measured by collimated FREND/DSEN. (a) Upper map is collimated for maximum resolution (200 km). (b) Lower map is omni directional (550 km). Black and white isolines correspond to WEH values. Adapted from Figure 2 of Malakahov, et al. [].

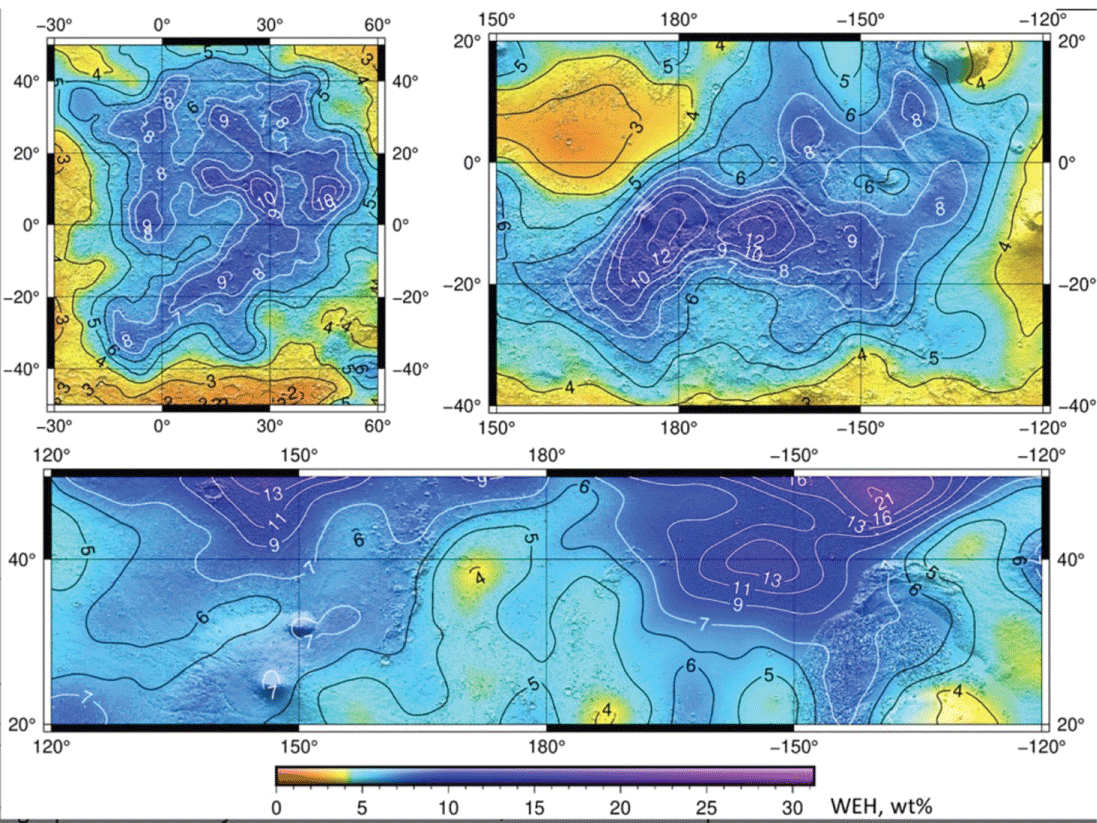

Figure 7: Water equivalent hydrogen maps, measured by collimated FREND/DSEN. (a) Upper map is collimated for maximum resolution (200 km). (b) Lower map is omni directional (550 km). Black and white isolines correspond to WEH values. Adapted from Figure 2 of Malakahov, et al. [].Malakahov, et al. [] selected three areas in Figure 7 to try to achieve even greater increased resolution, and the WEH contours for these three areas are shown in Figure 8. Figure 9 shows a comparison of how the improved resolution changed the map for the upper left plot of Arabia Terra in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Enhanced segments of the global map shown in Figure 7, showing details of three areas with most water content: Arabia Terra (top left), Medusa Fossae (top right) and Arcadia Planitia (bottom). Adapted from Figure 3 of Malakahov, et al. [].

Figure 8: Enhanced segments of the global map shown in Figure 7, showing details of three areas with most water content: Arabia Terra (top left), Medusa Fossae (top right) and Arcadia Planitia (bottom). Adapted from Figure 3 of Malakahov, et al. []. Figure 9: Comparison of the Arabia Terra segment of the WEH map at highest resolution to map at 200 km resolution. The small areas with WEH = 10% increase in size. Adapted from Figures 2 and 3 of Malakahov, et al. [].

Figure 9: Comparison of the Arabia Terra segment of the WEH map at highest resolution to map at 200 km resolution. The small areas with WEH = 10% increase in size. Adapted from Figures 2 and 3 of Malakahov, et al. [].The highest WEH was found in Arcadia Planita near 47° N latitude and 142° W longitude: an elliptical area of about 5 km x 10 km with apparent WEH = 21%. This was surrounded by a larger region that averaged WEH = 16%. The next greatest values of WEH elsewhere in the ±50° latitude range was typically in the 8% to 12% range.

An impression of the uncertainties in the WEH estimates is provided in Figure 10. If the uncertainty at any location is σ, the upper plot shows the most probable value –σ and the lower plot shows the most probable value +σ. If we focus on the blue area between longitude 0° and 30°, the maximum value in the upper plot is WEH = 9% and the maximum value in the lower plot is WEH = 13%, suggesting an uncertainty of about ±2%.

Malakahov, et al. [] noted several local areas with greater than average WEH. Two areas with the highest apparent WEH were: WEH = 23% at -17° N latitude, and WEH = 24% at 8° N latitude. The authors suggested that random errors accumulated, and the actual values might be about 16%. In both cases, the outline of high WEH follows the altitude contours quite closely. They also discussed other interesting sites where the outline of WEH follows the local terrain. In their discussion they pointed out the enigma that on the one hand, one does not expect relict ice to remain in the upper meter at low latitudes, but on the other hand, this would require a very large endowment of hydrated minerals that is not confirmed by IR observations. They also noted that this area occurs at low elevation compared to surrounding areas.

Figure 10: Minimum (a) and maximum (b) Water Equivalent Hydrogen (WEH) maps accompany the mean WEH map on Figure 8 and show the range of possible values, considering the measurements uncertainties with +σ and -σ. Adapted from Figure 5 of Malakahov, et al. [].

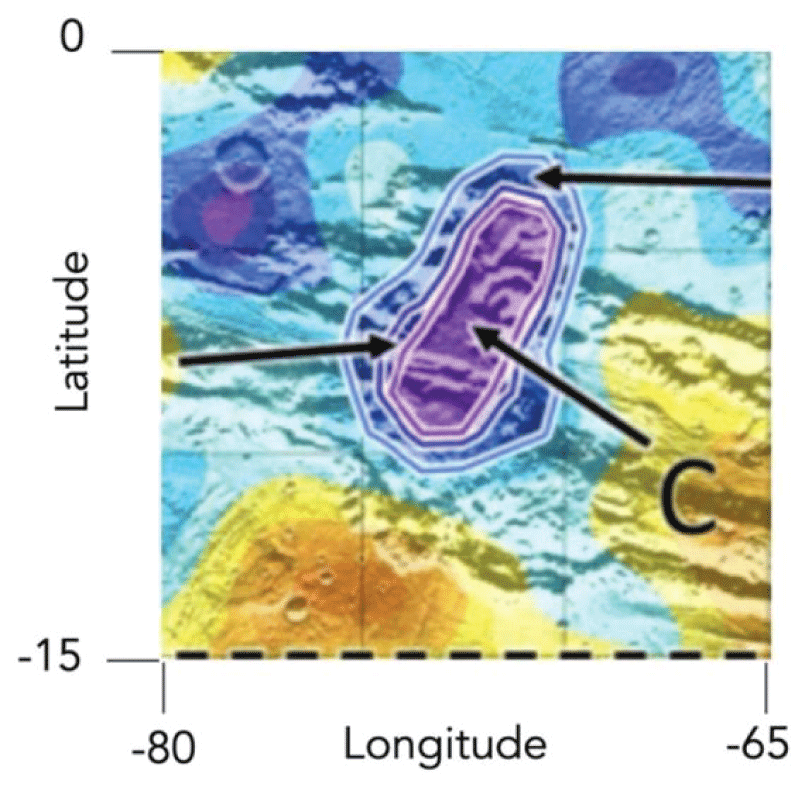

Figure 10: Minimum (a) and maximum (b) Water Equivalent Hydrogen (WEH) maps accompany the mean WEH map on Figure 8 and show the range of possible values, considering the measurements uncertainties with +σ and -σ. Adapted from Figure 5 of Malakahov, et al. [].Mitrofanov, et al. [] focused on a small area (about 400 km x 250 km) in the Valles Marineris at around longitude 72°W and latitude 7°S. Pushing their resolution to the highest possible value, they found an average WEH of 40.3% in this area (Figure 11).

Figure 11: The small (purple) region with observed 40.3% WEH. Adapted from Figure 1 of Mitrofanov, et al. [].

Figure 11: The small (purple) region with observed 40.3% WEH. Adapted from Figure 1 of Mitrofanov, et al. [].We then wondered how this compared to the upper plot in Figure 7. We overlaid Figure 11 on Figure 7, and the result is Figure 12. The red rectangle in Figure 12 is the boundary of Figure 11. The yellow roughly elliptical curve represents the purple area from Figure 11. The red square is the size of a 200 km pixel for Figure 7 Something seems amiss. Considering the size of a 200 km pixel in Figure 7 as shown by the red square, the data in Figure 7 might have had enough resolution to pick up the putative region of 40.3% WEH claimed by Mitrofanov, et al. []. The plot in Figure 7 shows about 6%. The very hi-res plot does not seem compatible with the 200-km resolution plot.

Figure 12: Water equivalent hydrogen map, measured by collimated FREND/DSEN – collimated for maximum resolution (200 km). The small area studied by Mitrofanov, et al. [] is superimposed as a yellow elliptical curve. Adapted from Figure 2 of Malakahov, et al. [] and Figure 1 of Mitrofanov, et al. [].

Figure 12: Water equivalent hydrogen map, measured by collimated FREND/DSEN – collimated for maximum resolution (200 km). The small area studied by Mitrofanov, et al. [] is superimposed as a yellow elliptical curve. Adapted from Figure 2 of Malakahov, et al. [] and Figure 1 of Mitrofanov, et al. [].Several studies using spectroscopy from Mars orbit identified places on Mars with high concentrations of hydrated minerals. Interestingly, these tend to cluster near the region with high hydrogen content, but not in it. As Mitrofanov, et al. [] pointed out, heavily hydrated magnesium sulphate can contain more than 50% H2O by weight. To explain the observed 40.3% WEH in terms of sulfate hydrates, one would have to postulate a very high concentration of the hydrate – which the authors thought was unlikely. The mean elevation of the WEH rich area is –1,455 m (relative to the MOLA Datum) and is a minimum near the center of the region. In the end, they concluded that they could not distinguish between hydrated minerals and ice embedded in the top 1 meter of regolith.

Figure 10 shows that relatively higher hydrogen concentrations occur in three (blue) longitudinal regions in the latitude range ±50°. These tend to run the full gamut of latitude but are each limited to a 60° range of longitude.

Jakosky, et al. [] explored the quantitative connections between the regolith water abundance and each of the physical properties that might be controlling the abundance. They estimated the degree of correlation between each of the physical parameters: (a) abundance of water as measured by neutron spectrometer, (b) annual peak abundance of water vapor, (c) mean annual surface temperature, (d) topography, (e) mean annual water vapor corrected for topography, (f) thermal inertia, (g) mean annual water vapor uncorrected for topography, and (h) albedo. Data were compared between latitudes of ±45° latitude only. They found a notable lack of statistical correlation between water abundance and any of the parameters, either singly, or in groups. They concluded: "no single parameter is able by itself to explain a significant fraction of the water distribution."

However, Putzig, et al. [] provides a plot of thermal inertia that some what resembles Figure 10 in that the thermal inertia tends to be lower in the regions of higher hydrogen abundance. Regions with low thermal inertia are cooler and might be more conducive to ice longevity.

Mars is believed to have had liquid water in the very distant past. Water on Mars today occurs either as vapor, bounded water in regolith, ice and hydrated minerals.

Prior to the last ~ 300,000 years, water was periodically transported between the poles and the temperate regions of Mars as the obliquity varied, and at times, near-surface water ice was stable in temperate regions. Most of the near surface of Mars regolith was endowed with great amounts of ice during this period. As the obliquity retreated and stabilized somewhat in the last 300,000 years, near-surface ground ice became theoretically unstable to sublimation in temperate zones, and although much of that ground ice disappeared over the many years, significant ground ice remained at some locations.

Acquisition of a source of indigenous water on Mars would provide vital support for various conceptual human missions [-]. We need not elaborate on that point. Searching for water on Mars is a challenging endeavor, and it is useful in the beginning to make synoptic analyses and observations to characterize the overall distribution.

Several scientists analyzed the process by which ice is lost from regolith to the atmosphere, which at any locality depends mainly on the vapor pressure of water, the thermal inertia of the soil, and the orientation and slope of the surface. For average conditions, near-surface ice is not expected to be thermodynamically stable at latitudes less than perhaps 55° to 60°. Yet, it is known from observation of ice ejected from some craters by impacts, that some near-surface remnant ice remains at various moderate locations on Mars (See Section 5.). This provided incentive to analyze heavily sloped (slope up to 30°) [,], North-facing slopes and indeed they concluded that ice might be stable to much lower latitudes at such extreme slopes. This seems to be a bit of sidetrack because 30° slopes are rare, they are not attractive for landing sites, and the calculations are approximate. The real point is that even though equilibrium thermodynamics indicates ice is unstable at some locations, the rate of loss might be exceedingly slow. The models basically tell us that if we find ice in temperate zones, it is probably due to slow kinetics. They also suggest that it is highly unlikely to find near-surface ice in the equatorial zone (± 30° latitude).

Models are useful, but observations are better. In a breakthrough, the Mars Odyssey Team used neutron spectroscopy from orbit to map essentially the top ~1 m of the whole planetary surface of Mars. Their observations detected hydrogen, which could be due to hydrated minerals or ground ice. The results were roughly in line with the analyses. Heavy concentrations of hydrogen were found poleward of +60° and -60° latitude, and in a few local regions, as low as ~ 45°. In addition, lower (but non-negligible) concentrations of hydrogen were found in various area in the equatorial zone (± 30° latitude). The limitation of these observations was the low resolution with a pixel of about 550 km in dimension. A region 550 km x 550 km with low average hydrogen might be broadly low in hydrogen or might contain a few small areas with very high hydrogen content. In general, one suspects that the hydrogen at the lowest latitudes is probably mineral hydrates; yet without ground truth verification, one can only guess. Subsequently, an excellent Russian Team carried out further studies using neutron spectroscopy from orbit in a Russian-European mission, that significantly improved the resolution of the observations (broadly 200 km x 200 km, and in a few specific places claimed to be approaching 60 km x 60 km). They concentrated their observations on temperate and equatorial sites. Almost all their measurements in the equatorial region are compatible with mineral hydrates and probably likely to be so. In a couple of small equatorial sites, the apparent hydrogen concentration was so high as to challenge the possibility of mineral hydrates. However, when one compares the very highest resolution maps to lower resolution maps, they don’t seem to be compatible, and it is not clear to us how valid the highest resolution (60 km) maps might be.

The neutron spectra measurements are important but suffer from two limitations: (1) they don’t detect hydrogen much deeper than ~ 1 m, and (2) the low resolution hides local areas of high hydrogen concentration.

Zheng, et al. [] briefly summarized the working principles of Martian ground-penetrating radar:

“The radar antenna emits radar pulses towards the subsurface of Mars. When the radar electromagnetic waves encounter differences in impedance from subsurface materials, reflections and scattering of the electromagnetic waves occur at the interfaces between different materials. These echo signals are then captured by the radar antenna. The data received by the radar are then analyzed to calculate the subsurface stratification and thickness of the soil on Mars, as well as the dielectric properties of the subsurface material, such as the value of dielectric loss and relative permittivity. By determining the polarization of the radar signal, it is potentially feasible to ascertain the presence of water ice in the superficial layers of the detection area. By processing these echo signals, the subsurface structure of the Mars surface and the composition of the subsurface materials can also be revealed” [].

Orbiter-based radars such as MARSIS, SHARAD, and MOSIR have a wide areal detection range. Penetration depths vary from about 0.1 km to 1 km. SHARAD has been orbiting Mars on the MRO since 2006.

The following is abstracted from Virkki, et al. []:

Electromagnetic waves are capable of penetrating into most natural materials up to hundreds of wavelengths, depending on the nature of the material, before being absorbed. Radar can penetrate into dry regolith and ice up to kilometers depth in some cases. If a dielectric discontinuity is present within the material, part of the wave is backscattered, and can be detected by a receiving antenna. This property has been used in radio echo sounding, or ice-penetrating radar, an established geophysical technique that has been used for more than five decades to investigate the structure of ice sheets and glaciers in Antarctica, Greenland, and the Arctic. Subsurface dielectric discontinuities in the form of layered sedimentary deposits or volumetric inclusions are imaged at resolutions of tens of meters. The Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS) and the SHAllow RADar (SHARAD) were the first to utilize this technique to explore the subsurface of Mars, and more recently by the Mars Orbiter Subsurface Investigation Radar (MOSIR). In addition, water ice within a layer is detected by its unique dielectric constant that distinguishes it from dry regolith.

The Medusae Fossae Formation (MFF) is located on Mars at 130–230°E and 12°S–12°N, straddling the equator. Shallow Radar (SHARAD) aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), identified distinct layers well below the surface in the MFF. Watters, et al. [] argued that it is difficult to explain the observations based on compositions of volcanic ash, eolian sediments, or dust. Compaction models of such fine-grained materials are in disagreement with observed dielectric and density measurements. Instead, Watters, et al. [] argued for a multi-layer ice-poor upper layer some 300 m to 600 m thick, overlaying an ice-rich layer at least 1 km thick, representing a potential volume of water-ice equivalent to be 1.5– 2.7 m global equivalent layer (GEL). Fastook, et al. [] justified the interpretation of radar signals as buried ice, reasoning that several billion years ago, the Mars obliquity could have reached ~40° for a few million years and during this period, the MFF region might have accumulated snow/ice in excess of a km. Subsequent ablation of this ice deposit surface in the several billion year-long period that followed, episodic eolian stripping of MFF protective sublimation residues and dust/tephra deposits, provides a mechanism sufficient to form the thick capping layer. If indeed this proves to be a buried ice deposit, that is very impressive – but unlikely to be useful for practical application. While it is not totally beyond conceivability, it seems very unlikely that this resource would be of any practical use in the near term or even mid-term. Nevertheless, this discovery was provided as a press release under the title “Buried water ice at Mars's equator?” with 47,000 views and 95 “likes” [].

Putzig, et al. [] and Bramson, et al. [] oddly seem to be similar papers published on the same study with the same results – but with two slightly different sets of authors. This study used radar to determine the apparent dielectric constant of the sub-surfaces of a large number of so-called terraced craters in the Arcadia Planitia (at latitude range 38–52°N and longitude range 165°–210° East) across 1 million km2. By a rather intricate process that was not completely understandable to us, they concluded that the measurements typically represented strong ice signals for tens of meters from the surface downward in hundreds of terraced craters. From that, they suggested a veritable ocean of ice embedded in regolith across 1 million km2 in the Arcadia Planitia at 38 – 52°N. They did not clarify specific observations at the lowest latitudes.

Bramson, et al. [] reported on radar reflectors as evidence of ice sheets at the Utopia Planita and the Arcadia Planita in the latitude range ~40°N to ~ 50°N. The reflectors were mostly ~100 m deep at the Utopia Planita but they were mainly around 50 m deep at the Arcadia Planita. They modeled the subsurface as a top desiccated layer, below which was a regolith layers with pores filled with ice (about 25% to 35% porosity), and below that was an “excess ice sheet”. The estimated thickness of the excess ice layer was 30 m to 80 m at Arcadia Planitia and 80 m to 170 m at the Utopia Planitia deposit. It was not clear how deep these excess ice layers are, but if the radar reflectors occur at the interface of the pore-filled and excess ice layers (only a guess because the article was unclear) then the excess ice layers would seem to be buried 50 m to 100 m.

These papers, like so many papers on discovery of ice on Mars, seems heavily endowed in optimism, which might be justified, but they ought to be approached with a bit more caution. They also ought to be much clearer on the estimated depth of various layers.

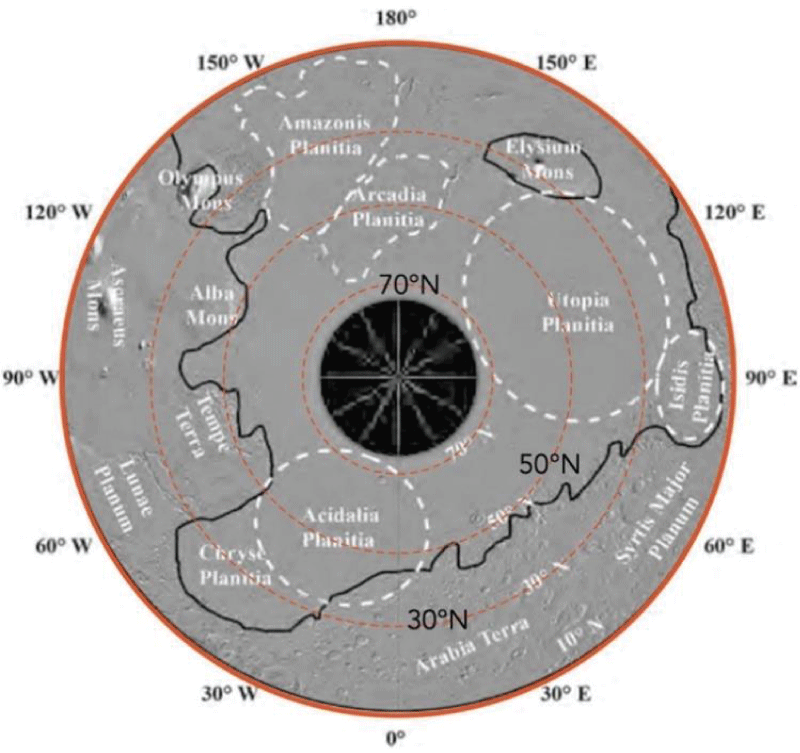

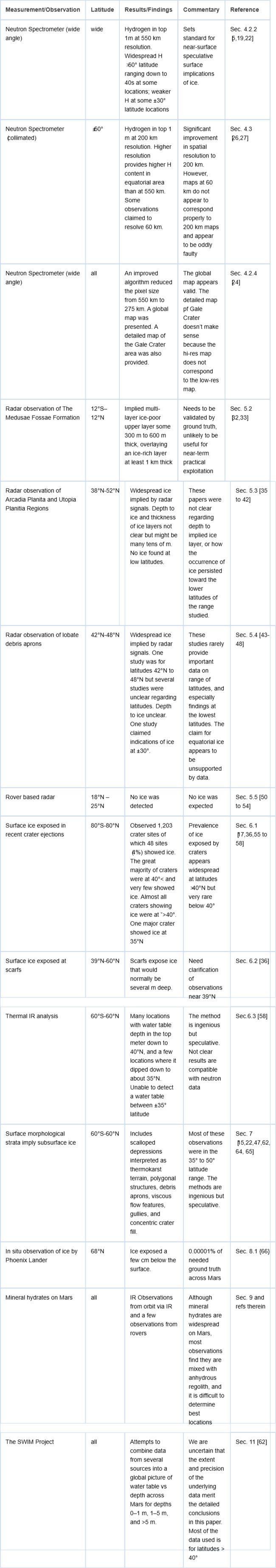

Gou, et al. [] carried out an extensive review of data on layered ejecta craters (LECs) at the planitas: Acidalia, Chryse, Utopia, Isidis, Amazonis, and Arcadia. These regions are illustrated in Figure 13. The data is summarized in Table 1. While there is a great deal of water tied up as ice, most of it is too deep to be practical in the near-term to mid-term.

Figure 13: Water equivalent hydrogen map, measured by collimated FREND/DSEN – collimated for maximum resolution (200 km). The small area studied by Mitrofanov, et al. [] is superimposed as a yellow elliptical curve. Adapted from Figure 2 of Malakahov, et al. [] and Figure 1 of Mitrofanov, et al. [].

Figure 13: Water equivalent hydrogen map, measured by collimated FREND/DSEN – collimated for maximum resolution (200 km). The small area studied by Mitrofanov, et al. [] is superimposed as a yellow elliptical curve. Adapted from Figure 2 of Malakahov, et al. [] and Figure 1 of Mitrofanov, et al. [].They also pointed out that others had found related results. For instance, one early study inferred the depth to the top of an ice-rich layer where LECs are initially observed (“roof depth”) to be about 300–400 m at 30° latitude and decreases to about 50–100 m at 50°. Another found the roof depth varies regionally within ±30° latitude range and could be as shallow as 110 m in Solis and Thaumasia Planae. Yet another estimated the subsurface ice table in the equatorial region of the Valles Marineris plateaus to be between ~75 m and ~ 260 m.

Stuurman, et al. [] used radar to investigate the Utopia Planitia (spanning approximately 375,000 km2 (35–50°N; 80–115°E). They found widespread areas with a radar reflector perhaps 50 to 120 m below the surface and they were able to estimate the dielectric constant for the subsurface above the reflector. The described these upper layers as “layered mesas”, which term despite their best efforts, still leaves us confused. They claimed the evidence showed that the layered mesas were heavily laden with ice. In their conclusions, they said:

“The presence of a water ice deposit 80–170 m thick and approximately 375,000 km2 in area in western Utopia Planitia is supported by radar evidence... The material overlying the reflective interface found in this work is estimated to be 50% - 85% water ice by volume. We estimate a water ice volume of approximately 8,400–14,300 km3 within the layered mesas” [].

One very important aspect they did not report was the latitudinal distribution of the icy area. The word “latitude” occurs 15 times in the paper, but there doesn’t seem to be any information on the latitudinal extent of the observations, especially the region below 40°N. Another factor they did not discuss at all was the depth of any overburden before the ice begins. These two factors are the most important for any ice distribution and somehow the authors did not report on them.

Hibbard, et al. [] combined several lines of investigation (expansive radar reflective region with high densities of scalloped depressions and polygonal terrain) to justify the RADAR findings spanning approximately 375,000 km2 in (SHARAD) data over western Utopia Planitia.

None of the above papers clarified the range of lower latitudinal data or the depth of overburden, which is the most important information involved. Indeed, this vital data is often missing from reports of ice on Mars.

Wang, et al. [] imagined a subsurface structure for the Utopia Planita involving 1 m of dry Colian sediment, atop about 0.7 m of ice-bearing Colian sediment, atop about 0.5 m of ice-bearing Basalt sediment. We were unable to connect this model any real data.

Ma, et al. [] investigated possible existence of subsurface water ice at low latitudes of Mars. SHARAD radargrams for late-Amazonian-aged impact craters were studied. They systematically investigated subsurface structures of layered ejecta deposits (LED) that were formed by 27 late-Amazonian-aged impact craters at low latitudes of Mars. The selected craters have pristine preservation states, and their LED were wide and thick enough to be resolved by SHARAD. Their results show that nearly all the investigated craters exhibit no discernible subsurface reflectors, suggesting little difference in dielectric properties between LEDs and surrounding terrain.

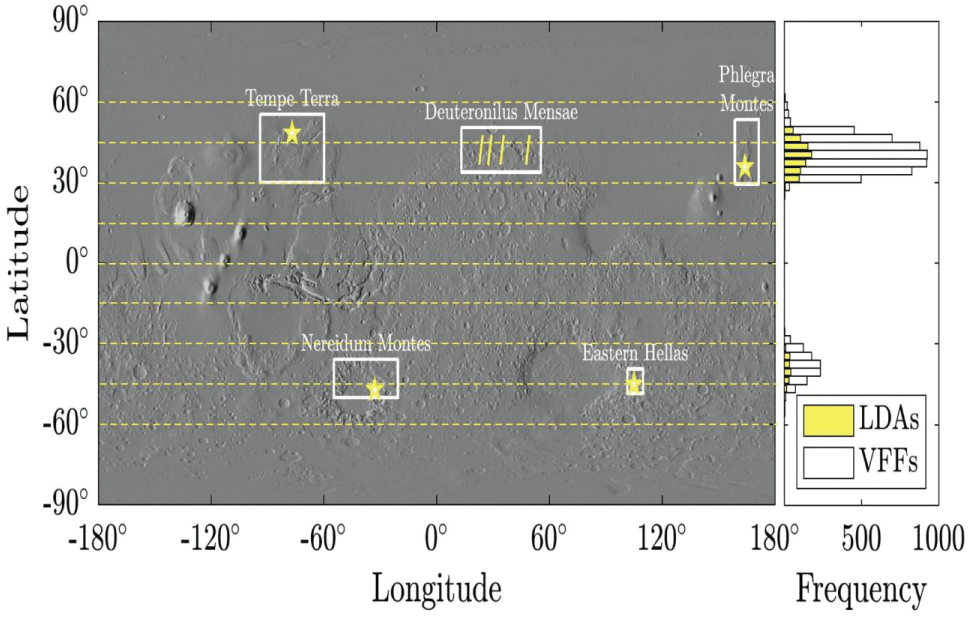

Lobate debris aprons (LDA) are dust and rock-covered Martian landforms thought to contain buried water ice due to their resemblance to creeping permafrost and debris-covered glaciers on Earth.

Plaut, et al. [] described Martian surface features identified as lobate debris aprons (LDAs) as thick (100s of m) masses of material that extend up to several 10s of km from high relief slopes and terminate in lobate (curved) fronts. They presented new evidence from the Shallow Radar (SHARAD) sounding experiment on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) that LDAs in the Deuteronilus Mensae region (centered at 41°N, 26°E) consist mostly of ice. They described the area as “mid-northern latitudes” but did not specify the exact range.