Abstract

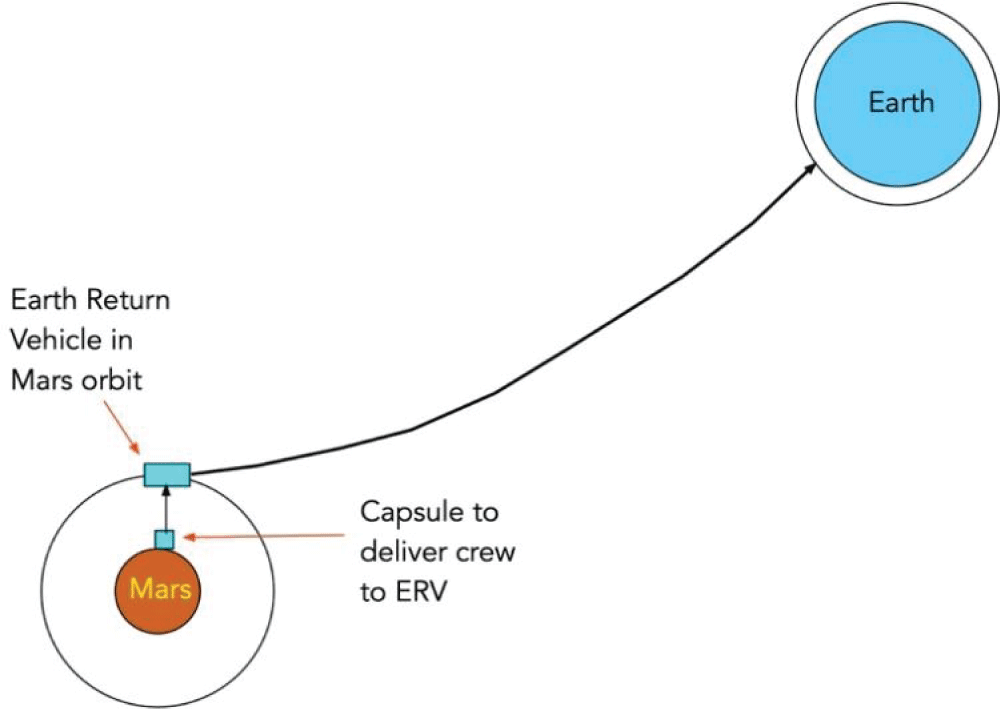

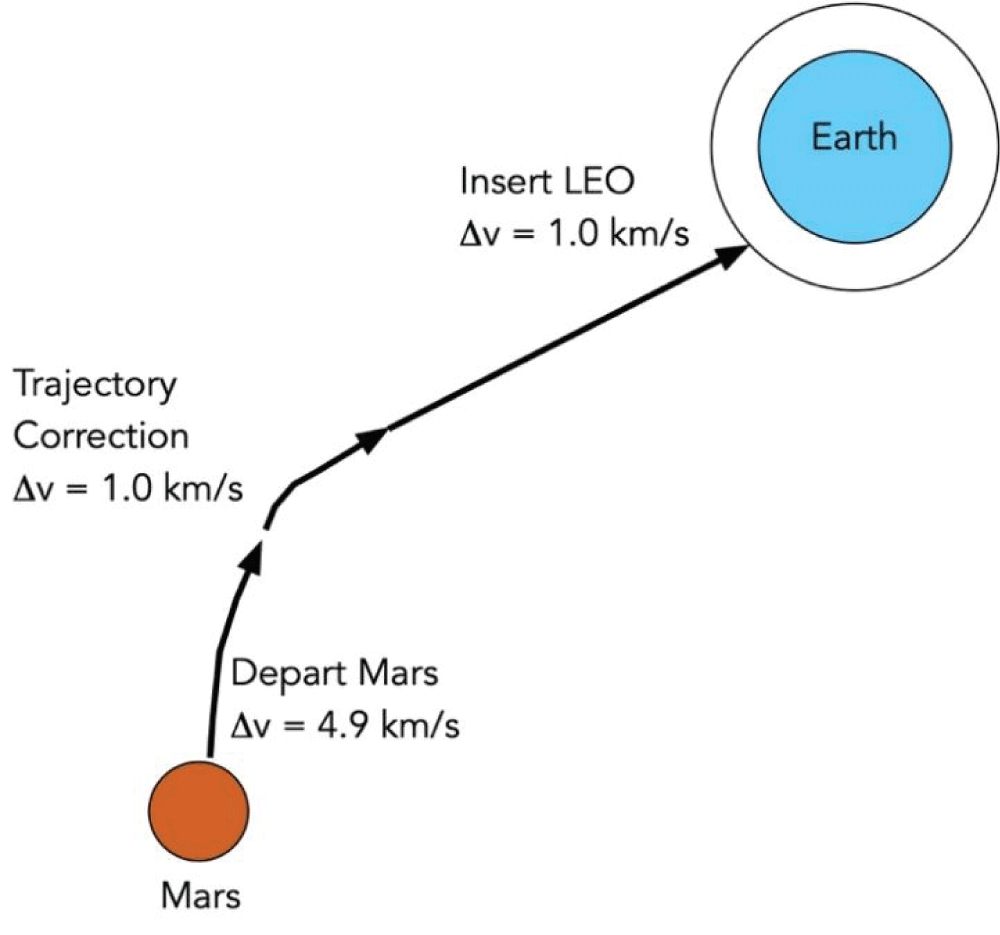

NASA teams have clarified requirements for a landing site for the first human mission to Mars regarding important factors such as elevation, slope, winds, rock abundance, radar reflectivity, etc. Current planning in the NASA for a landing site for human missions to Mars community is aimed at mission architectures that utilize accessible H2O on Mars to produce several hundred tons of propellants for the return trip using the Starship. This limits the acceptable range of latitude to about 40°N, where observations from orbit suggest that accessible H2O might occur. In this paper, it is shown that a simpler, less demanding architecture for the first human landing on Mars could be carried out without requiring accessible H2O on Mars. With this mission model, the landing site could be chosen at an equatorial site, with several benefits in energy, thermal stability, and solar psychological environment, while avoiding the challenges of locating, verifying H2O, and validating and implementing processes for utilization. Proof of the existence of such accessible H2O requires ground truth, not yet attempted. It is suggested that NASA teams should also consider equatorial landing sites for mission architectures that do not require indigenous Mars H2O, which might be preferred for the first landing.

Layman’s explanation

With the advent of newly evolving very large, affordable launch vehicles, plans for the first human expedition to Mars have become focused on very ambitious mission concepts that require large amounts of indigenous Mars ice to produce propellants for the return flight from Mars – a significant challenge, complication, and cost and risk additive. This limits potential landing sites to non-equatorial latitudes, which introduces several disadvantages. I propose a smaller, less ambitious mission plan for the first human landing on Mars that doesn’t require Mars ice and therefore could land near the equator. I analyze the water supply for such a mission.